Travel Notes – Iceland

Cheap, Reliable Energy Makes for Prosperity

Faithful readers will have noted that there has been a bit of a hiatus in my posts. I have been travelling for the past almost four weeks, and, frankly, I didn’t want to interrupt my time visiting grandchildren in Japan and then discovering the east coast of Australia for the first time.

Now, having boarded the long flight from Sydney to Vancouver, it is time to reengage.

I will finish off the series of posts I started on energy literacy[1], but before that, I thought I would post some notes on three countries visited over the past six months – Iceland in June, and Japan and Australia in October. Are there any lessons from these countries for Canada? Let’s see.

This post will focus on Iceland.

Iceland

Mindful that a short-term tourist’s impression isn’t a totally reliable authority on the social and economic health of a country, the Iceland we saw looked to be a “rich” society economically, socially and culturally. One felt safe walking the streets, and we saw little of the urban social problems that are now quite prevalent in Canada. The people we interacted with were helpful and friendly in a non-obtrusive way. Meals seemed a little expensive, though that may be as much a factor of the weak Canadian dollar as Icelandic affordability problems.

These impressions reinforce more objective measurements. Iceland ranks 1st out of 193 countries in the most recent U.N. Human Development Index,[2] and 3rd out of 147 in the most recent World Happiness Report.[3]

And, lest we think they take themselves too seriously, there is the “Monument to the Unknown Bureaucrat” in Reykjavik. I am sure anybody who has been a public servant anywhere can relate to that.

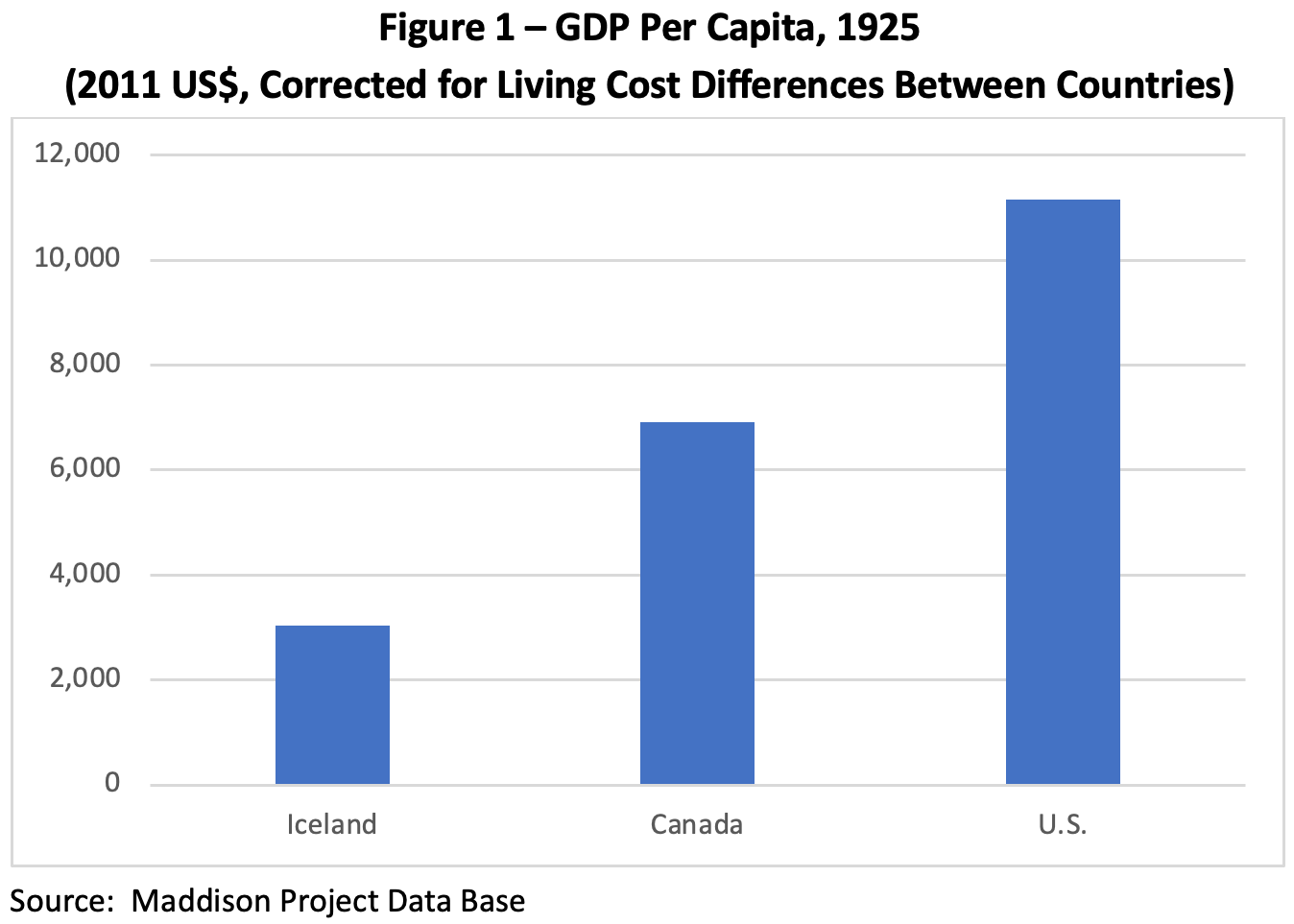

If we go back 100 years, however, Iceland was not rich at all. In 1925, Iceland’s GDP per capita was only 44 percent of Canada’s, and 27 percent of that of the U.S., as shown in Figure 1 below.

The reasons for this relative poverty are fairly straightforward. Iceland had limited agricultural potential because of its northern latitude – the only farm product it was able to export was wool - limited mining potential, and sparse (to say the least) forest resources. It’s small population – in 1925 its population was approximately 100,000 - far removed from major economies meant there was no prospect of achieving economies of scale in manufacturing. There had been fairly rich fisheries, but with a limited ability to restrict access from the fishing fleets of other countries, these tended to be overfished and depleted. Throw in the occasional volcanic eruption and spells of colder than usual weather, and the future didn’t look all that great.

Indeed, thousands of Icelanders agreed, and between 1870-1914 it is estimated that 20-25% pf the population emigrated.[4] Canada was one of the beneficiaries of this outmigration - the Canadian Icelandic community, initially centred in the Interlake region of Manitoba has contributed significantly to Canada over the past century.[5] .

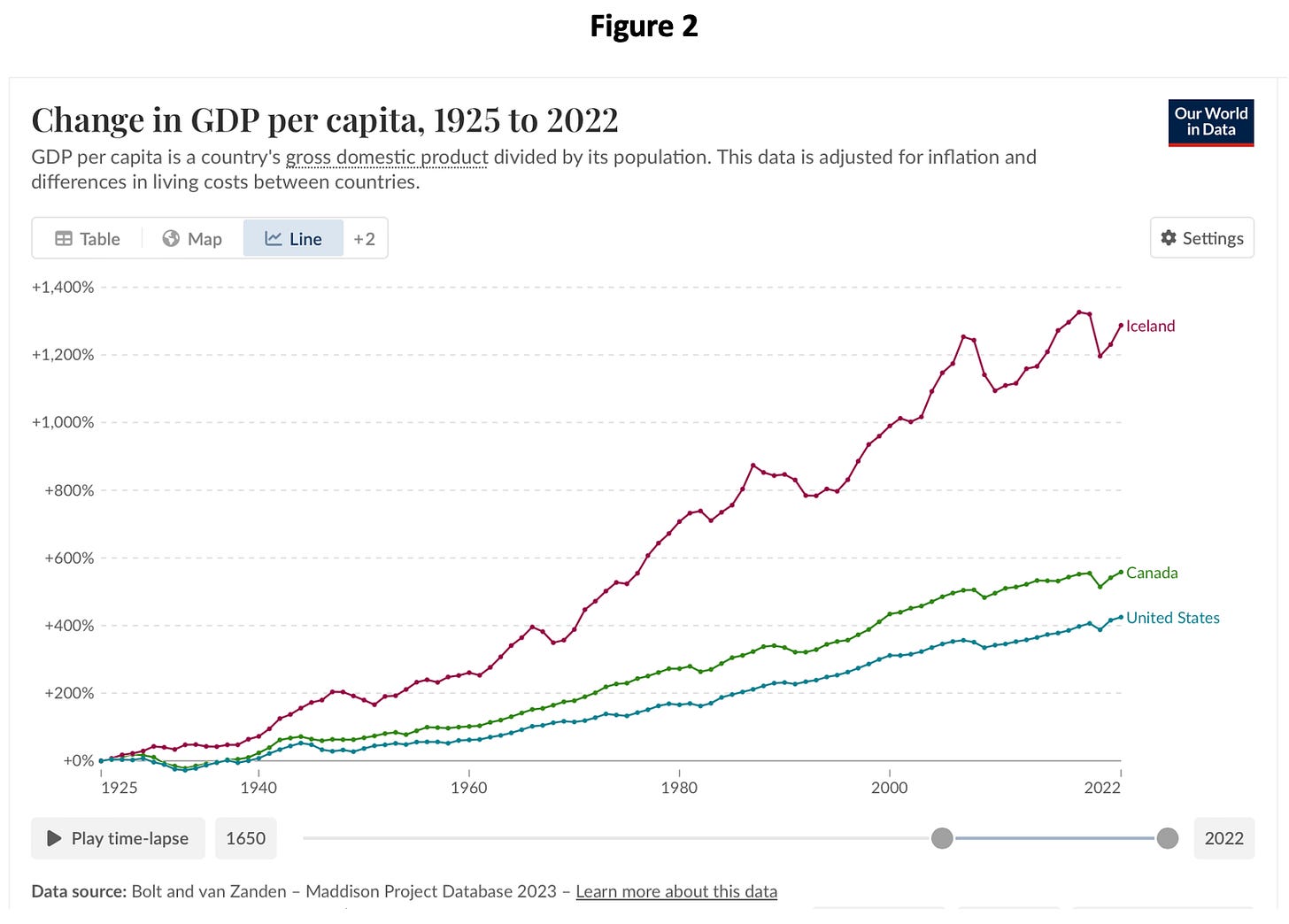

And yet, since 1925, Iceland’s relative economic performance has far surpassed that of both Canada and the U.S., as shown below in Figure 2.

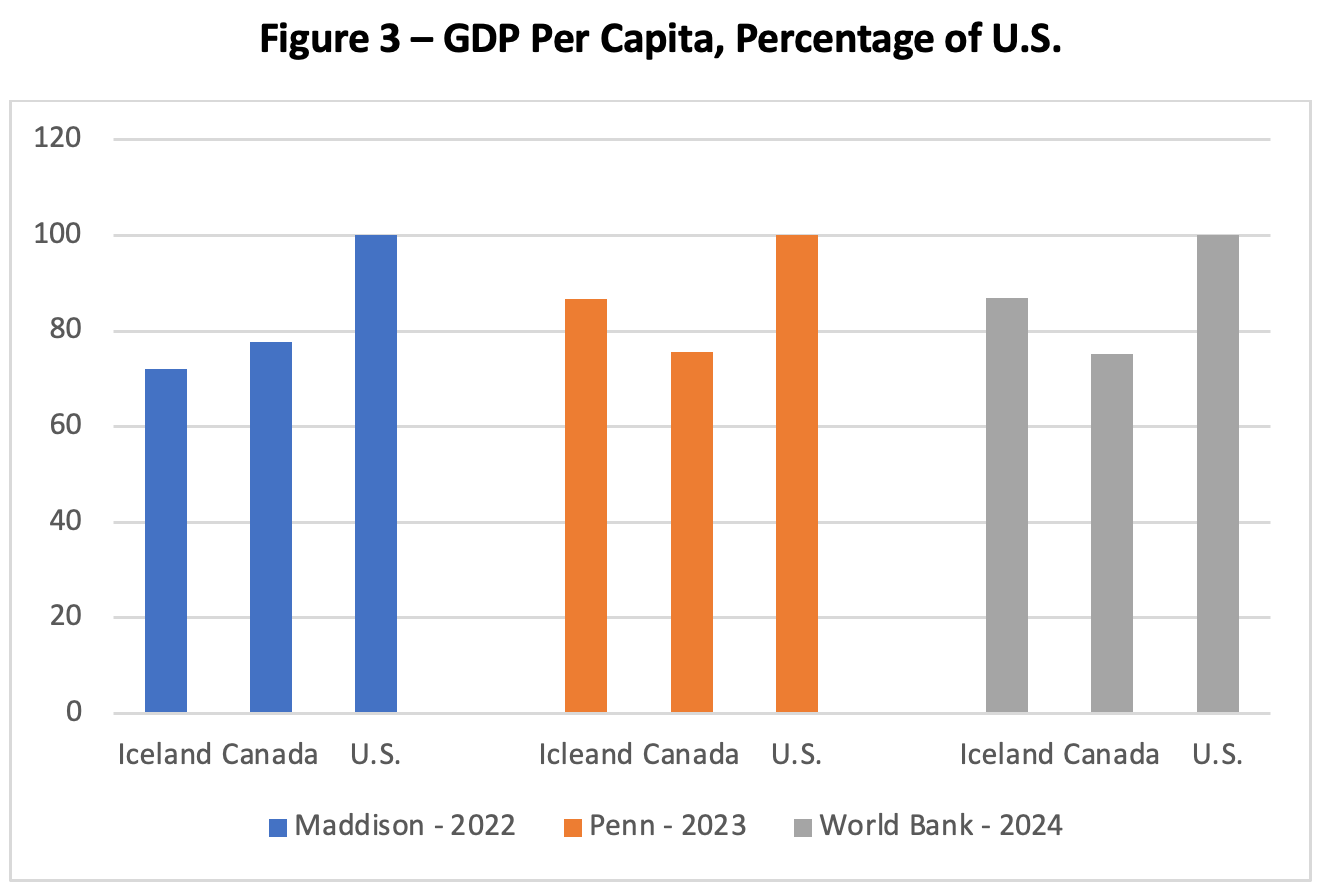

Figures 1 and 2 are based on the Maddison Project Database, which is the only source for comparative data going back more than 75 years. But there are two other series – the Penn World Table and the World Bank which provide additional estimates. Figure 3 below shows the most recent year’s estimate for each of these series, with each country’s per capita GDP expressed as a percentage of that of the U.S. in the same year.

Compare the relative height of the bars in Figure 3 to those in Figure 1. Iceland’s GDP per capita relative to Canada’s has gone from 44 percent in 1925 to between 93-119 percent in 2022-24 - two of the three series show Iceland’s per capita GDP, corrected for living cost differences, is now higher than Canada’s! Its GDP per capita relative to that of the U.S. has gone from 27 percent in 1925 to between 72-77 percent in 2022-24.

How did it achieve this remarkable catchup?

One Simple Answer

The inventory of Iceland’s weak natural resource base recited above left out one key element.

“Iceland lies on the divergent boundary between the Eurasian plate and the North American plate. It also lies above a hotspot, the Iceland plume. The plume is believed to have caused the formation of Iceland itself, the island first appearing over the ocean surface about 16 to 18 million years ago. The result is an island characterized by repeated volcanism and geothermal phenomenon.”[6]

Millions of years of volcanism has resulted in many high mountains in Iceland. These high mountains host many large glaciers. The spring and summer runoff from these glaciers provides an ideal setting for building hydroelectric dams which can generate electricity on a fully dispatchable basis – the water flowing through the dams can be metered out over the year, and day-to-day, to match consumption needs.

The first hydroelectric dam in Iceland was built in 1904, but large-scale harnessing of the hydroelectric potential didn’t get fully underway until after World War II, when a publicly owned corporation roughly equivalent to those of Canadian provinces – for example, Quebec Hydro - was set up.

But wait, there’s more! Another feature of Iceland’s geological origins is that hot magma is very close to the surface over large parts of the main island. While this does have a bit of a downside – i.e. the occasional volcanic eruption – it also has a big upside as well. It provides very favourable conditions to harness geothermal energy which also is very dispatchable. The geothermal energy is used both for heating purposes – geothermal district heating provides the heating for most Icelandic communities – and for electricity generation.

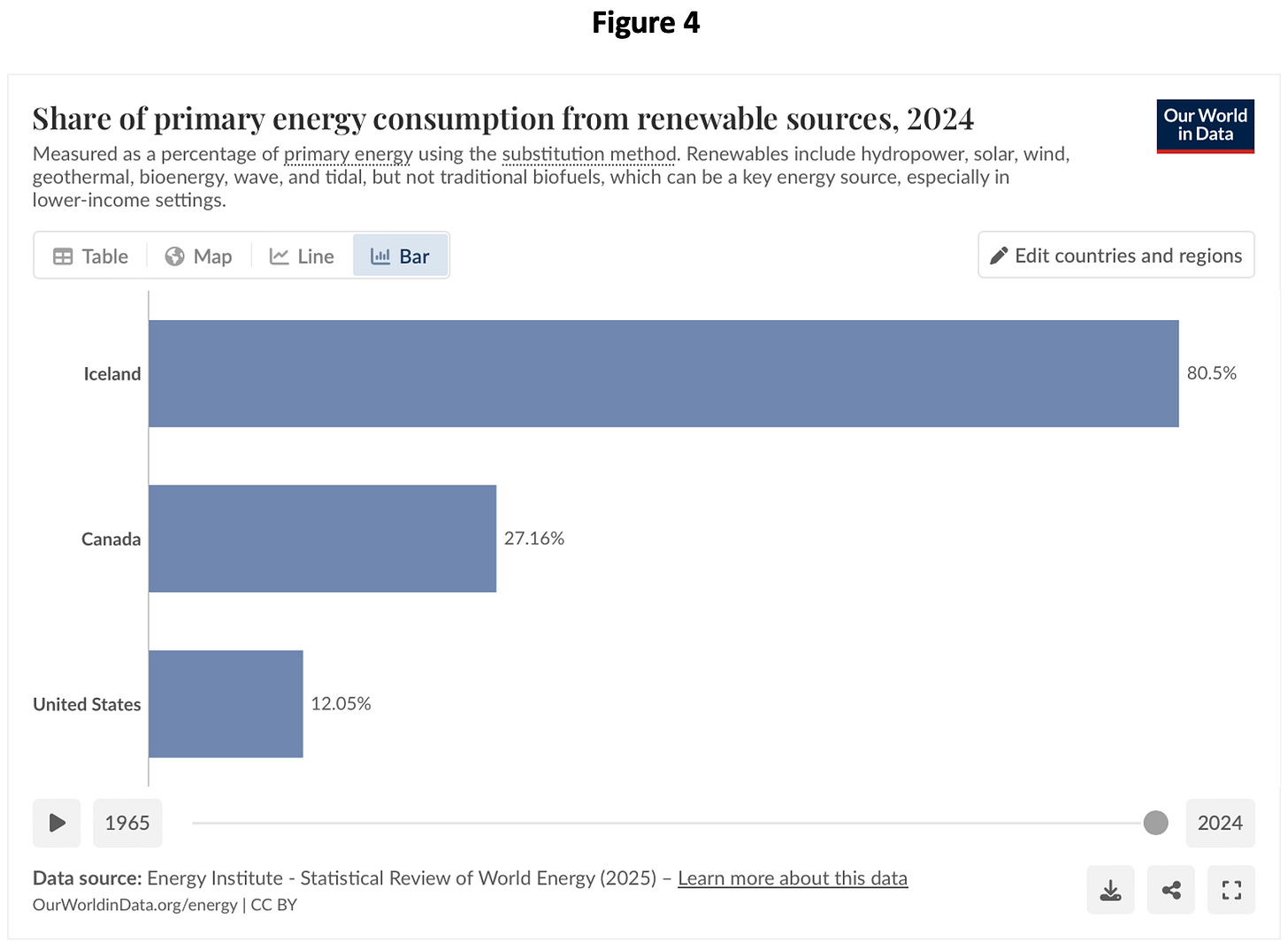

Overall, Iceland has the “greenest” energy mix of any OECD country. Figure 4 below compares the percentage of primary energy consumption from renewable sources in Iceland to the percentages in Canada and the U.S.

But, from a standard-of-living perspective, the most important feature here is that, per capita Iceland has a cornucopia of cheap, reliable energy. It has the least expensive electricity in Europe.

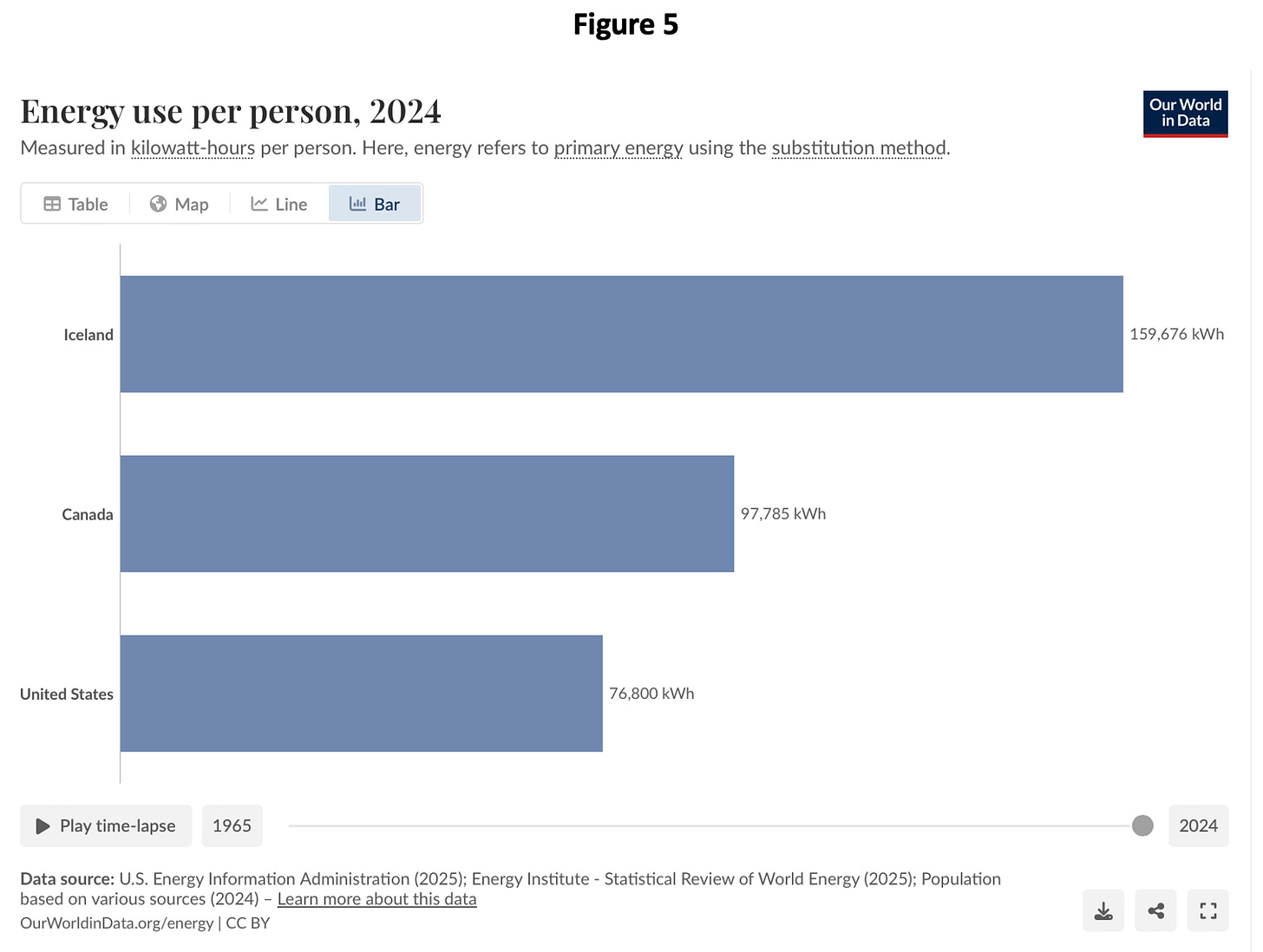

Furthermore, it has a whole lot of it. Figure 5 below compares the total energy consumption per capita in Iceland to that of Canada and the U.S.

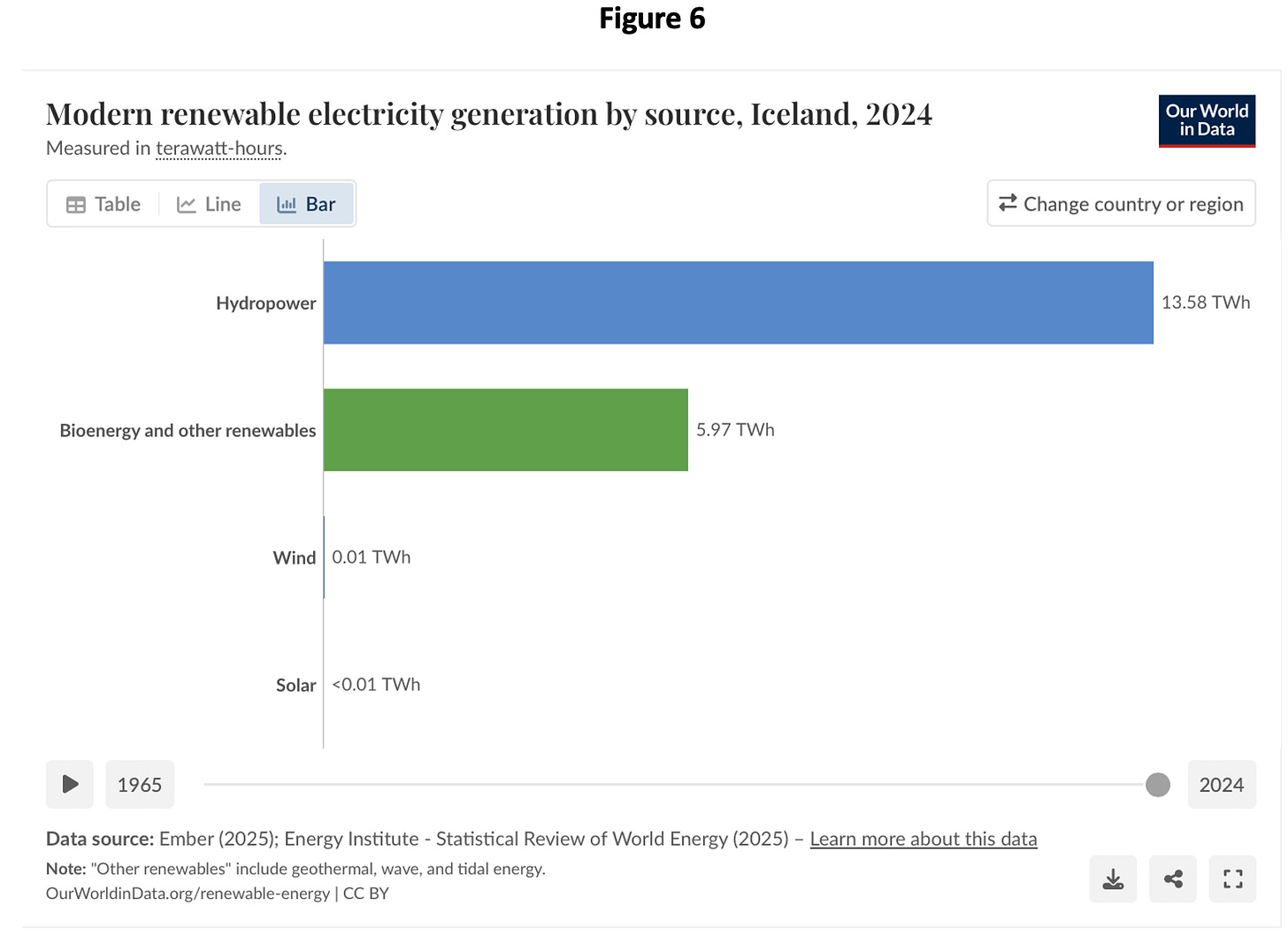

A side note: apparently, so-called cheap wind and solar doesn’t hold much appeal to a jurisdiction that has ample amounts of dispatchable hydro and geothermal generated electricity. Figure 6 below shows the percentages of Iceland’s electricity that is generated from different sources. (“Bioenergy and other renewables” is almost exclusively geothermal in Iceland’s case.) Interesting.

Iceland Has (Mostly) Spent It’s Energy Gift Wisely

So, our basic explanation for Iceland’s remarkable catchup to Canada and the U.S. is that it harnessed its latent cheap, reliable energy to compensate for its otherwise very unfavourable geography.

But it still had to make wise choices about how it decided to “spend” that energy gift. For example, it might have decided to try to compete in manufacturing automobiles, or in the manufacture of other products. Had it chosen that route, Iceland’s location disadvantages and small domestic market would have resulted in rather quickly squandering Iceland’s energy gift, with virtually no possibility of a competitive manufacturing sector.

What it chose to do instead was quite wise. There were several components to its approach:

1. The decision to keep hydro and geothermal largely under public ownership insured that the benefits of the energy gift would be shared by the population as a whole, rather than appropriated by private interests that were granted favourable site locations.

2. The maintenance of low energy costs provided a significant affordability benefit across all households and businesses.

3. The one industry that it did encourage – aluminum – is an industry for which low electricity costs are paramount. In a fundamental sense, the manufacture of aluminum is essentially the manufacture of embodied electricity. There is a reason why virtually all aluminum manufacturing in the world is situated where there is cheap electricity.[7] Aluminum is Iceland’s largest export.

4. As Iceland grew in prosperity in the post-war period, it was able to invest more in its coast guard and began to assert its sovereignty over its coastal waters. It “won” a series of “Cod Wars” with the U.K., and was able to extend its exclusive fishing zone to 50 kilometres from shore.[8] Having established this, Iceland was able to regulate its fisheries to maximize economic returns while maintaining sustainable fish stocks. Fish products are Iceland’s second largest export.

Of course, no jurisdiction is immune to stupid. In the first decade of this century, Iceland got swept up in the international banking craziness that came crashing down in 2008. Iceland seems to have gotten through the hangover from that wild party, and now seems to be back on a more prudent path.

Are the Lessons in this for Canada?

There are two basic lessons here.

First, a successful economic strategy needs to be built upon geographic reality. Factor endowments matter. Location matters. Relative population size matters. A successful strategy will be built on a realistic analysis of the types of economic activity a country can be competitive in, while paying high wages and generating healthy amounts of net government revenue. A theme we have discussed before.[9]

Secondly, we should never forget that cheap, reliable energy is really, really important. Another theme to which we will return.

[1] https://donwright.substack.com/p/energy-illiteracy-could-kill-us

[2] https://hdr.undp.org/data-center/country-insights#/ranks

[3] https://data.worldhappiness.report/table?_gl=1*1ykwtot*_gcl_au*MzU3MjY2OTYyLjE3NjE1NDY2MTg.

[4] https://www.hofsos.is/general-6

[5] On a personal note, my first economics professor, Leo Kristjanson, was from this community. He retired as President of the University of Saskatchewan in 1989.

[6]https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Geology_of_Iceland#:~:text=The%20geology%20of%20Iceland%20is,geothermal%20phenomena%20such%20as%20geysers.

[7] Parenthetically, this is why Donald Trump’s heavy tariffs on aluminum are particularly stupid. The U.S. does not have a surplus of low-cost electricity. In fact, if the build out of AI-linked data centres proceeds as projected, the U.S. will have the exact opposite.

[8] It was a pretty tame war. There were no fatalities. Iceland essentially won the war in the court of international public opinion.

[9] https://donwright.substack.com/p/lets-not-be-bad-economists

I love the monument to the unknown bureaucrat! Even more so, I love your message about spending an energy gift wisely.

I think a missing piece of this is that Iceland has a different political system than us - proportional representation. Studies of shown countries with proportional representation outperform their peers due to a greater emphasis on the wellbeing of the economy as a whole rather than geographically concentrated industries, and through a greater openness to trade. The gap is about 1% of growth per year on average, which really adds up over a long period of time.

Knutsen (2011) https://www.researchgate.net/publication/251540542_Which_democracies_prosper_Electoral_rules_form_of_government_and_economic_growth#fullTextFileContent

Afano & Baraldi (2015) https://www.degruyterbrill.com/document/doi/10.1515/rle-2015-0005/html?casa_token=GboRJaCzlocAAAAA:yOomf35nBX__Qoh72OQrbMjMX5eoCjskxDgGI7TjYf0tlHs7QiSMoWqE4HrHnP0qDrR3xYPrOt54tQ

Evans (2009) https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/j.1468-0343.2009.00346.x?casa_token=8BSUIViKvnwAAAAA:9nxsp8A4XLf2sdBSp9mlUz2vlOAA2aJbTjtfX84xc0Jm7z5iNFx2etZ0RZxJdNWSyumO-N9bX0gv8xud3Q