Energy Illiteracy Could Kill Us

"To see what is in front of one's nose needs a constant struggle"

George Orwell

Over the previous four posts we looked at some of the issues around Canada’s policies concerning seniors, population and immigration policies. There is much more to explore there, but, for now, we are going to shift our focus to Canadian energy and climate change policies.

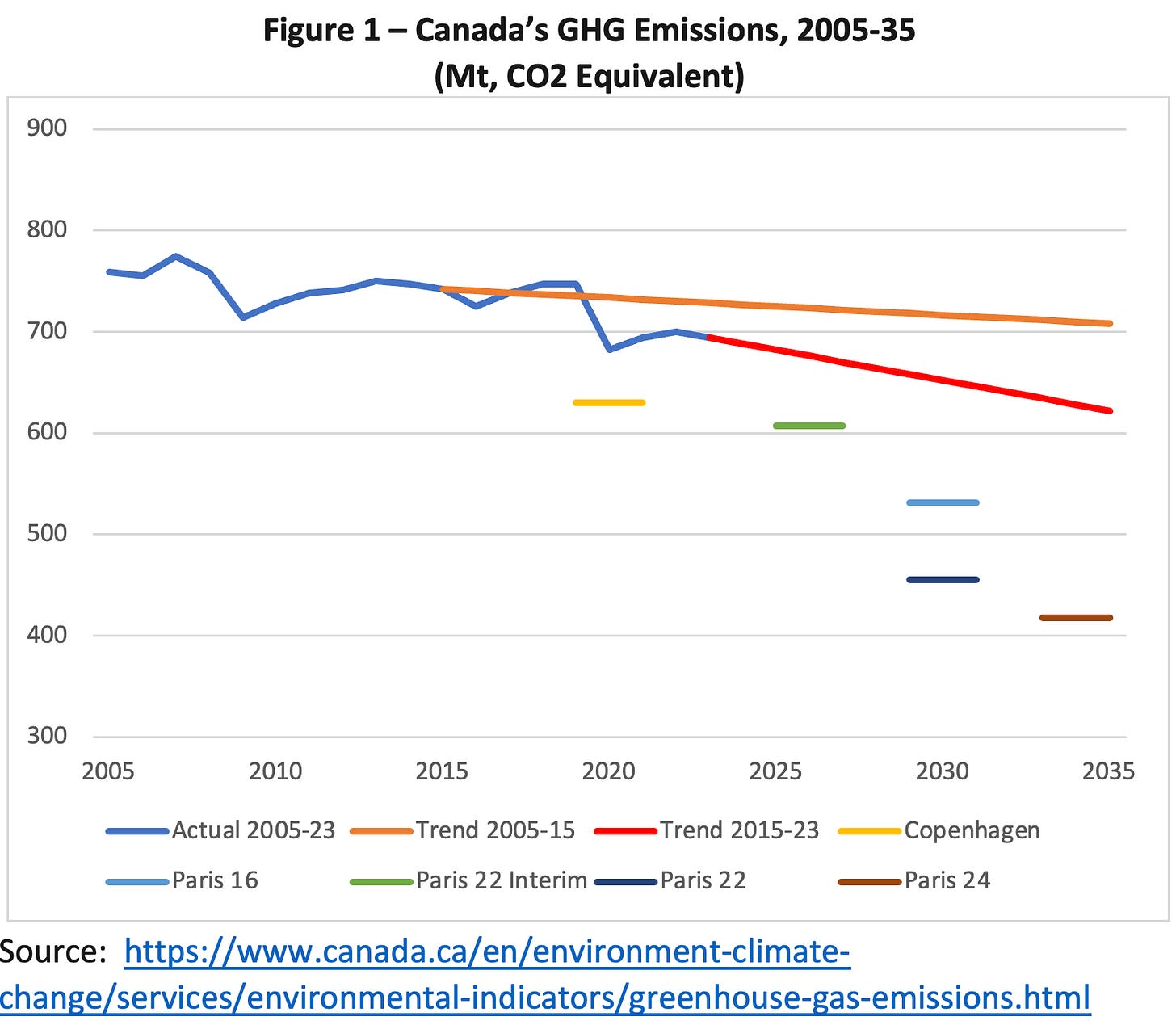

Since the early 2000s, Canada has been setting targets for reductions of Greenhouse Gas (GHG) emissions under the UN climate change process. The targets have grown increasingly ambitious:

· In the 2009 Copenhagen Accord Canada committed to 2020 GHG emissions 17% below its 2005 level;

· In 2016, following the 2015 Paris Agreement, Canada committed to 2030 emissions 30% below the 2005 level;

· In 2022, Canada upped its 2030 commitment to 40-45% below the 2005 level; it also established an “interim” target for 2026 of 20% below the 2005 level;

· In 2024, Canada added a commitment to be 45-50% below the 2005 level in 2035.

Under the Paris Agreement Canada also committed to be “Net Zero” by 2050.

How has Canada fared in living up to these commitments? Figure 1 below provides a take on answering this question. It shows the actual path between 2005-23, projects that path out through 2035 under two scenarios – one is to continue the trend from 2005-15 (the “Harper trend”), the other is to continue the trend from 2015-23 (the “Trudeau trend”). It also shows the targets just listed above.

The projection based on 2015-23 trend is probably somewhat flattering, as 2023 GHG emissions reflect, in part, the fact that the Canadian economy still hasn’t fully recovered from its post-pandemic malaise. On the other hand, proponents of the Trudeau government’s climate change strategy would argue that a number of the key components of that strategy – e.g., the clean electricity regulation and the oil and gas emissions cap – have not been implemented yet. The counter to that is that over the past 6 months there has been some walking back of policies previously implemented – e.g., the elimination of the consumer carbon tax and the postponement of the EV mandate – as well as speculation that there may be second thoughts on the clean electricity regulation and the oil and gas emissions cap.[1]

Canada did not meet its Copenhagen target, it is extremely unlikely that it will meet its 2026 interim Paris target, and factoring in all of the economic and political headwinds that are likely to challenge the federal government over the next few years, it seems quite unlikely that the 2030 and 2035 targets will be met.

This is despite extensive regulatory measures and government expenditures. In Canada’s most recent report to the UN, it claimed that “Since 2015, the Government of Canada has put in place over 140 measures across the country, and has committed over $160 billion to build Canada’s clean economy and reduce emissions.”[2]

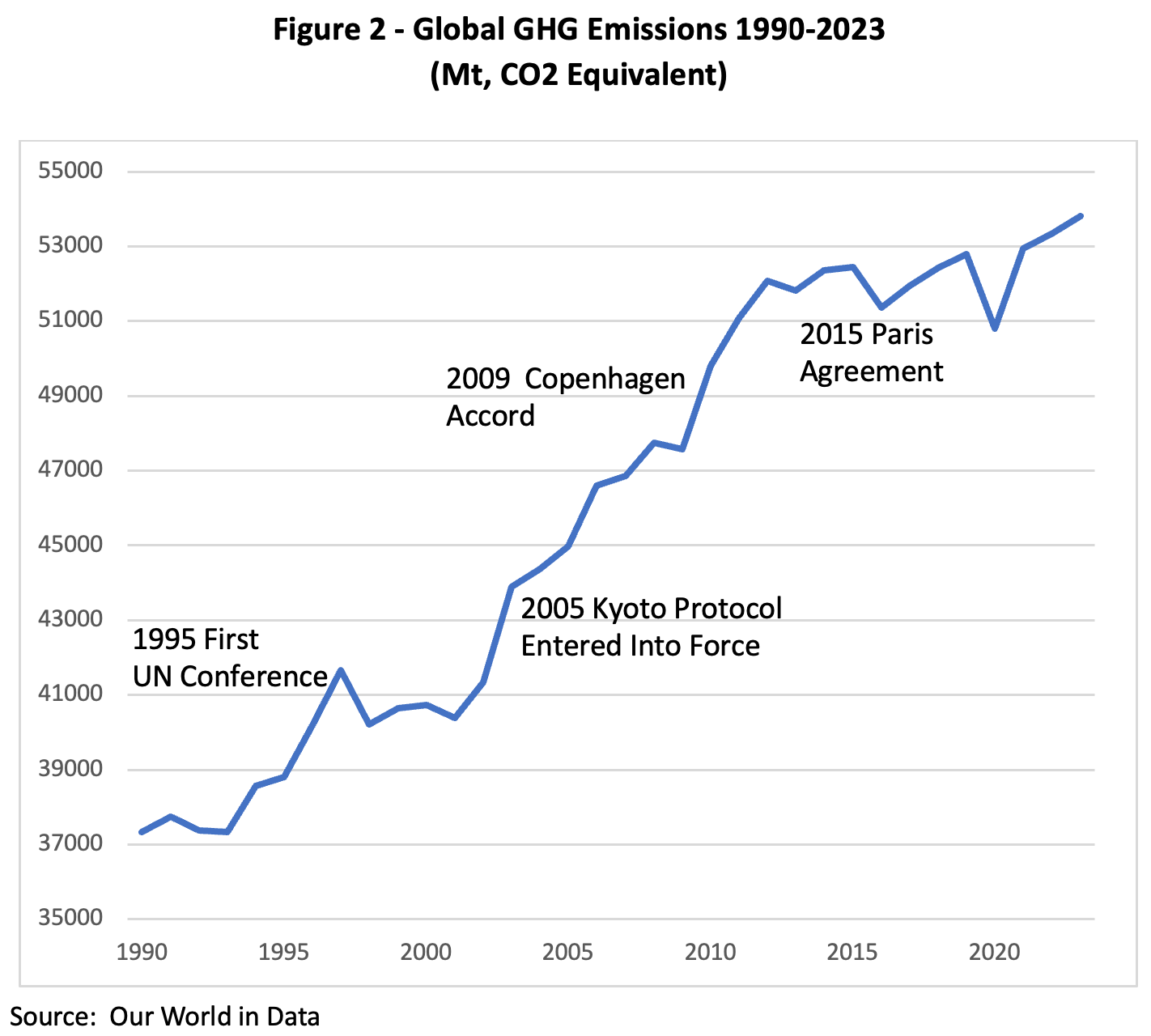

Lest we be too hard on Canada’s performance, it is important to point out that, notwithstanding all of the global climate change efforts of the past 30 years, there is little evidence that the world has begun to bend the emissions curve, as shown in Figure 2 below.

Twenty-nine annual UN “Conferences of the Parties,” and this is the best the world can do?

The basic problem here is that too much of what is put forward on the “energy transition” is not energy literate. By energy literacy I mean a comprehensive understanding of:

· the centrality of inexpensive, reliable energy, where and when it is needed, to the incredible increase in human well-being over the past 200 years;

· the relative costs of different forms of energy;

· the relative efficacy of different forms of energy in different uses;

· the complexity of energy systems; and

· the benefits, costs, and overall coherence, or lack thereof, of different approaches to transition.

Energy literacy is too frequently replaced by magical thinking and platitudes. If not rectified, this alarming degree of energy illiteracy could well kill us, not just figuratively but literally.

A Short Take on Long Economic History

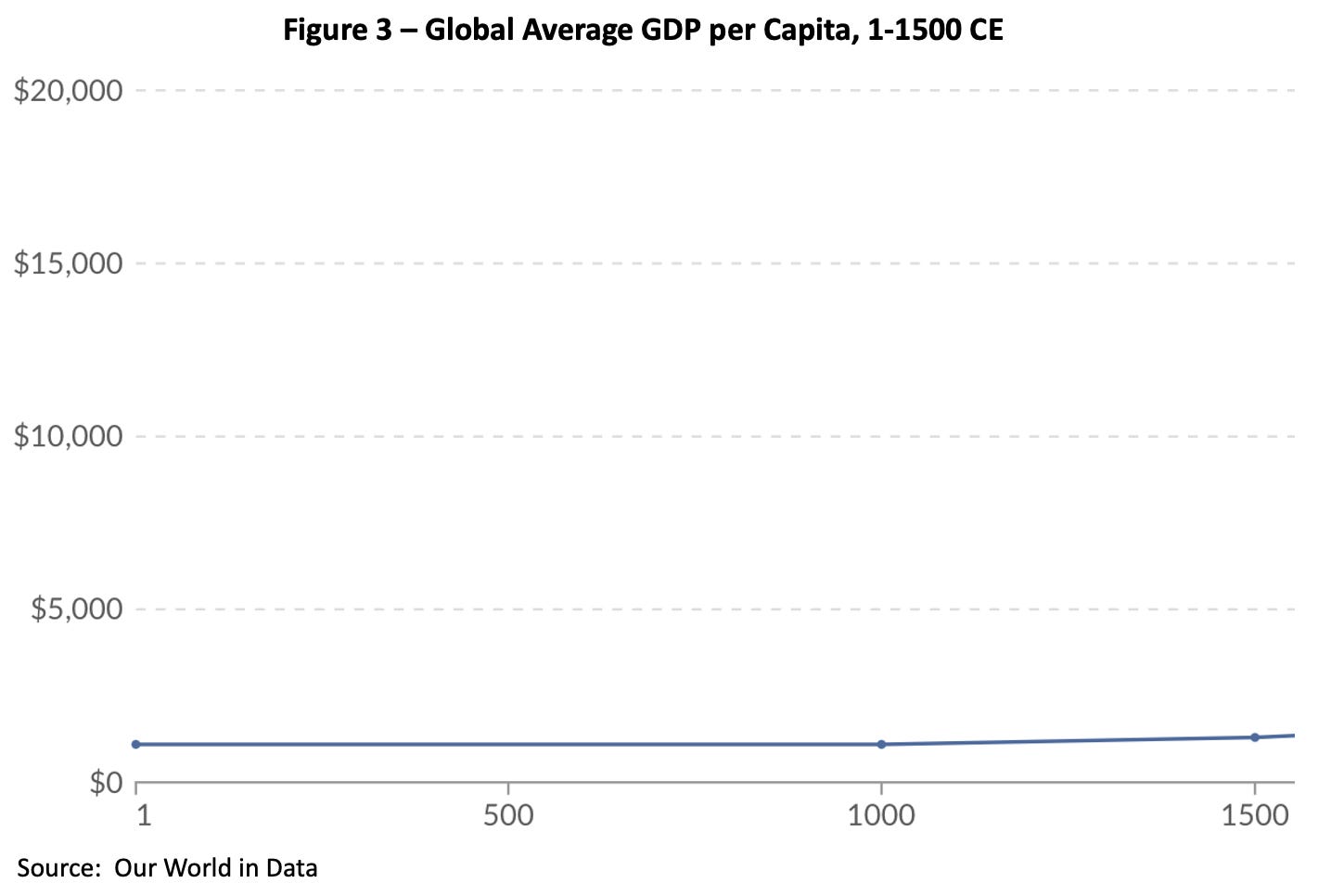

This post will make extensive use of figures from the wonderful site Our World in Data. Figure 3 below is a clip from one of their graphs which shows how world average GDP per capita evolved over the past two thousand years.

Not a lot happening, is there?

This is the best estimate of what the global average would have been, based on piecing together the evidence from a relatively few civilizations. Within any particular society there would be fluctuations around that average, but the Malthusian trap prevailed – those fluctuations were around the subsistence level of income. For most of human history, the vast majority of humans lived perilously close to bare subsistence. Only a small minority in any society lived above that level, based on a surplus that was extracted from the majority, through taxes, forced labour or chattel slavery.[3]

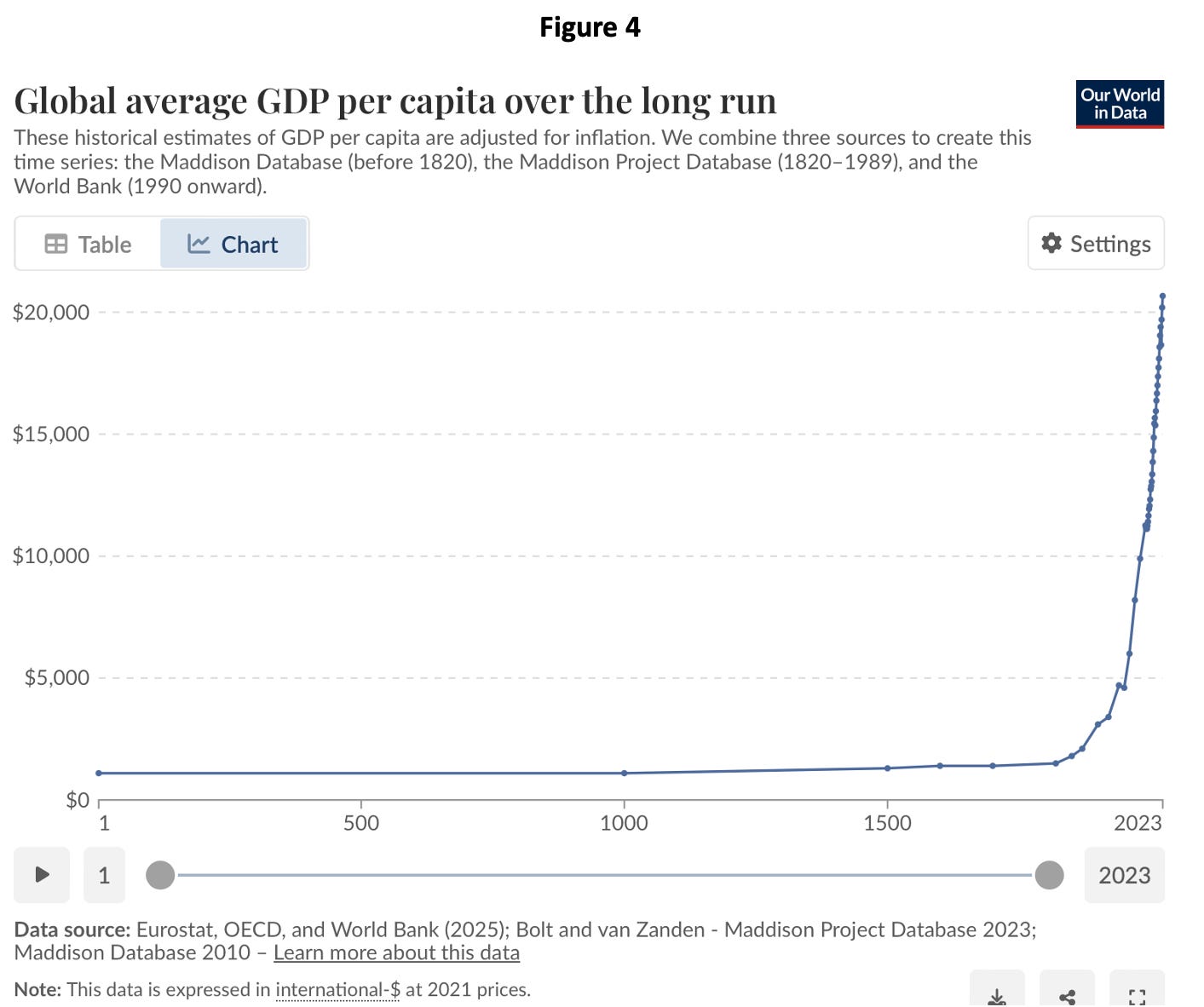

Now look at what happens when we add the rest of the graph in Figure 4 below.

Quite a different story emerges. After 1820 the curve starts to bend upwards, rising exponentially. At different rates in different parts of the world, societies broke out of the Malthusian trap.

What Led to the Breakout from the Malthusian Trap?

From the history-of-ideas perspective, the standard explanation for this is that the scientific revolution of the 16th and 17th centuries, and the industrial revolution in the 18th and 19th centuries provided the basis for escaping the Malthusian Trap.

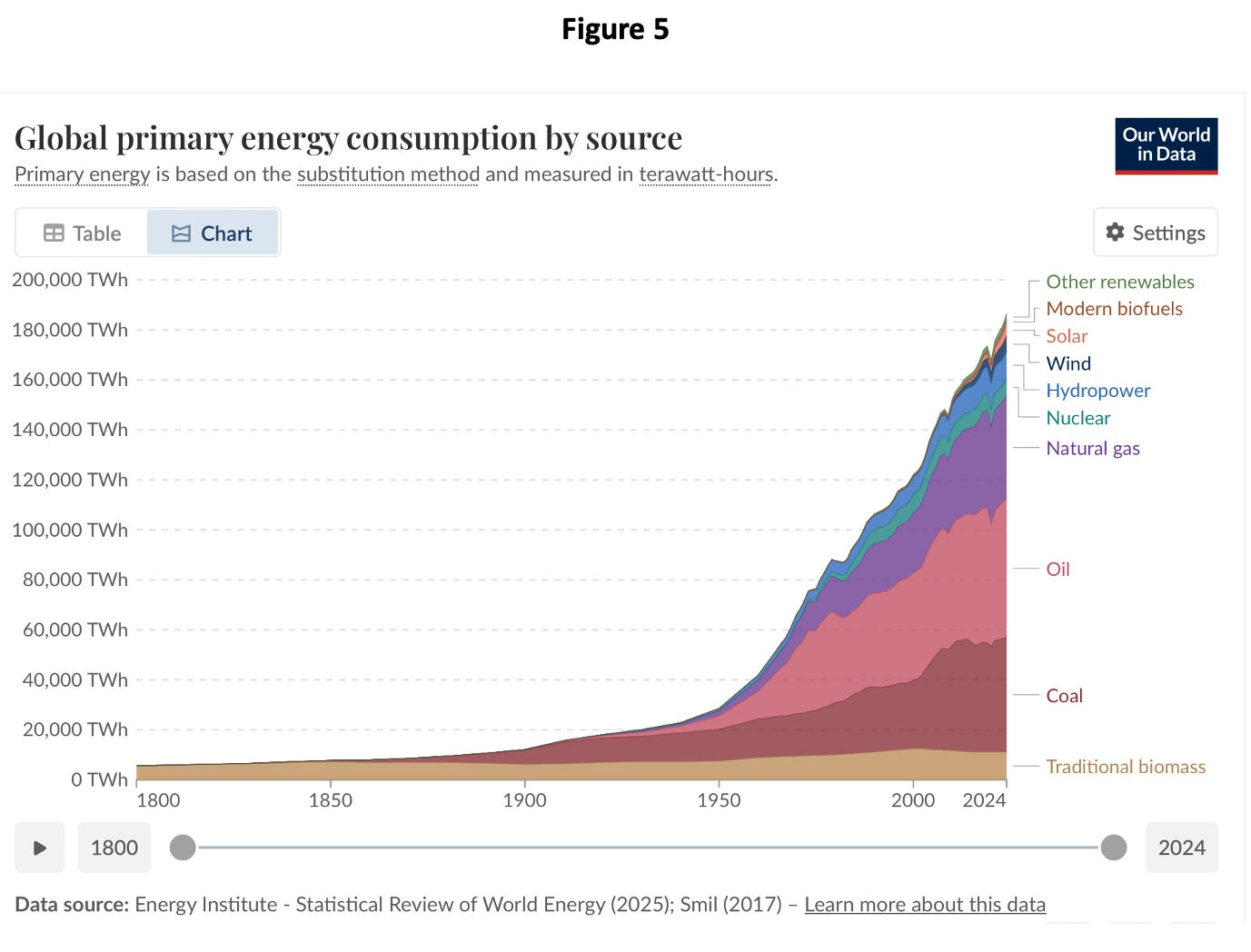

There is another perspective, call it the thermodynamic perspective. To understand what is meant by this, compare Figure 4 with Figure 5 below, which shows the total energy consumed in the world between 1800 and 2024.

At the start of the period shown here, burning traditional biomass – wood, crop waste, charcoal or dung – was the dominant source of inanimate energy. The amount of inanimate energy available was constrained by the physical work that humans and work animals could perform farming, harvesting wood, making charcoal or collecting dung, net of what was necessary simply to maintain survival of the humans and the work animals. The margins in this world – the work surplus to what was required to keep the humans and animals alive - were quite slim, which explains why the vast majority of humans for almost all of human history have lived close to the subsistence level, with only a small minority able to live a richer life.[4]

This all changed dramatically with the development of technologies that could harness fossil fuels. The physical work capacities of humans and animals were no longer the fundamental constraint on economic development. And GDP per capita began to grow. It is no coincidence that the exponential growth in GDP per capita starting after 1820 coincides with the rapid growth of coal use. Coal was subsequently supplemented with other sources of energy – oil, natural gas, hydroelectricity, nuclear, and over the past 20 years, growing amounts of solar, wind and other sources.

At a fundamental level, the explanation of the increasing standard of living of the past 200 years is a thermodynamic one. Ever increasing amounts of energy-dense inanimate sources have augmented human and animal muscle power. With the advent of artificial intelligence, which will require immense amounts of electricity to run the data centres that make it work, this process is moving to an even higher level, in which the same energy-dense inanimate sources will augment human brain power.

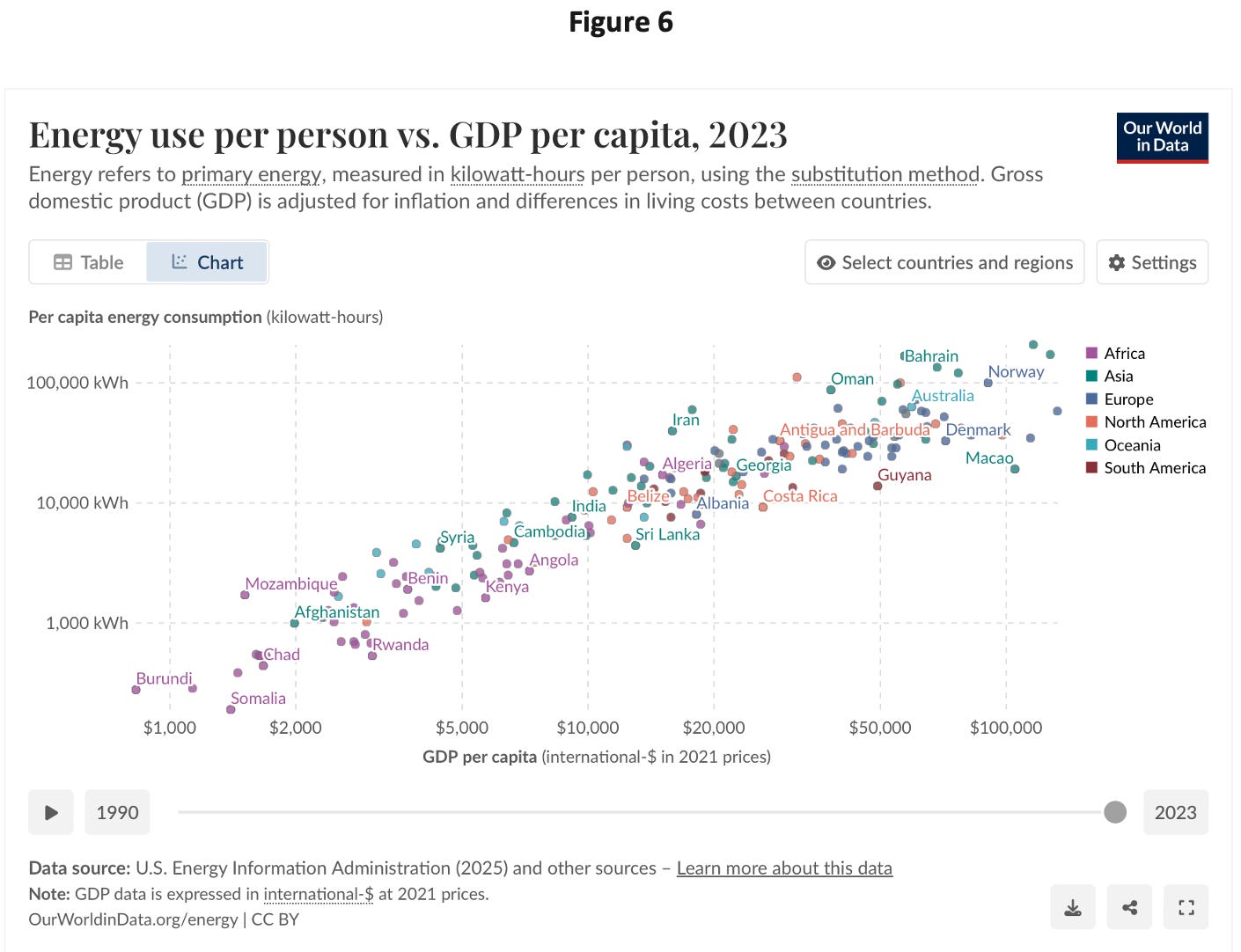

One way to think about this was first suggested by Buckminster Fuller when he introduced the notion of ‘energy slaves’ in an article in 1940. The notion is that the amount of work done by a human slave is now widely available through the labour augmenting power of modern inanimate energy sources. In 1950 he calculated there were approximately 38 energy slaves for every actual person in the world.[5] Using the same formula, I calculate there are now roughly 76 energy slaves for every living person. Those energy slaves are spread unequally around the world. Canadians “employ” approximately 340 energy slaves each. People living in the Central African Republic have access to only 1 energy slave each.

Does this mean scientific and technological progress have had nothing to do with the story? Of course not. Technological innovations that allowed the harnessing of these other energy sources – the canonical example here is the steam engine – were crucial to setting this all in motion. And there have been ongoing contributions from the development of other sources of energy and from the continuous improvement in energy efficiency.

But the key point remains – a higher standard of living has been built on the use of ever more inanimate energy, ever more efficiently. No high energy use, no high standard of living. There are no high-income-low-energy countries. Figure 6 below makes this clear.

Why Do We Care About This?

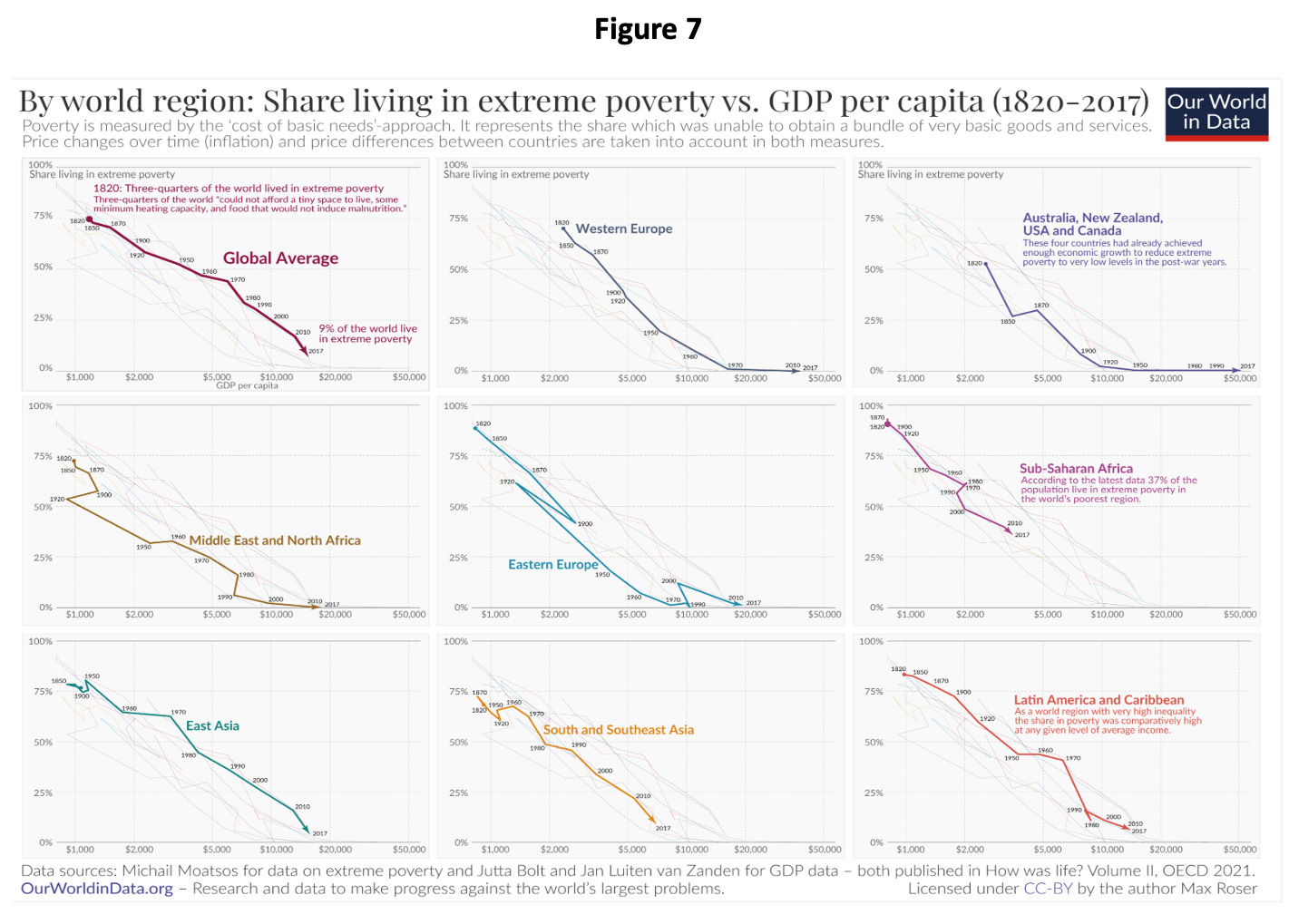

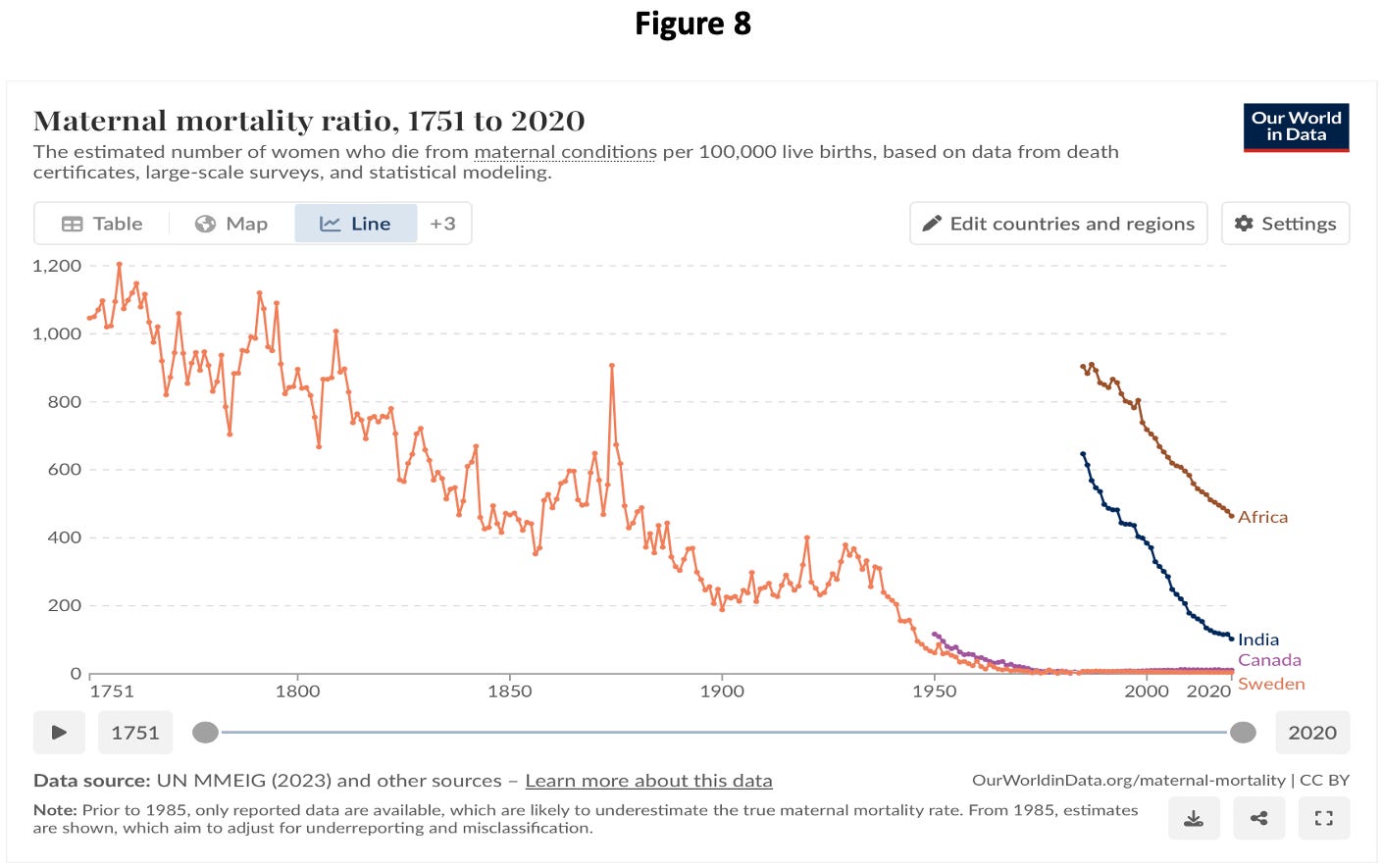

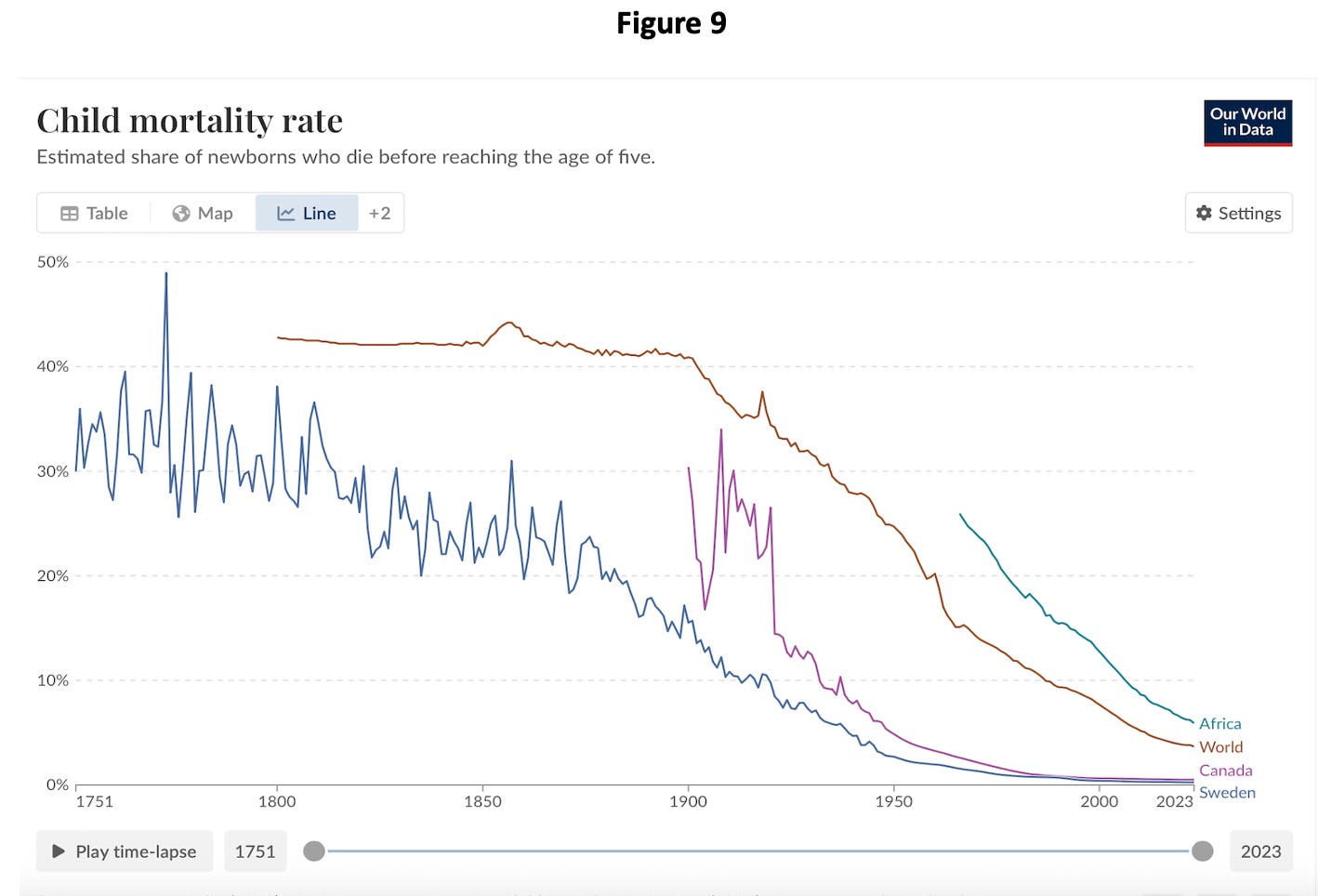

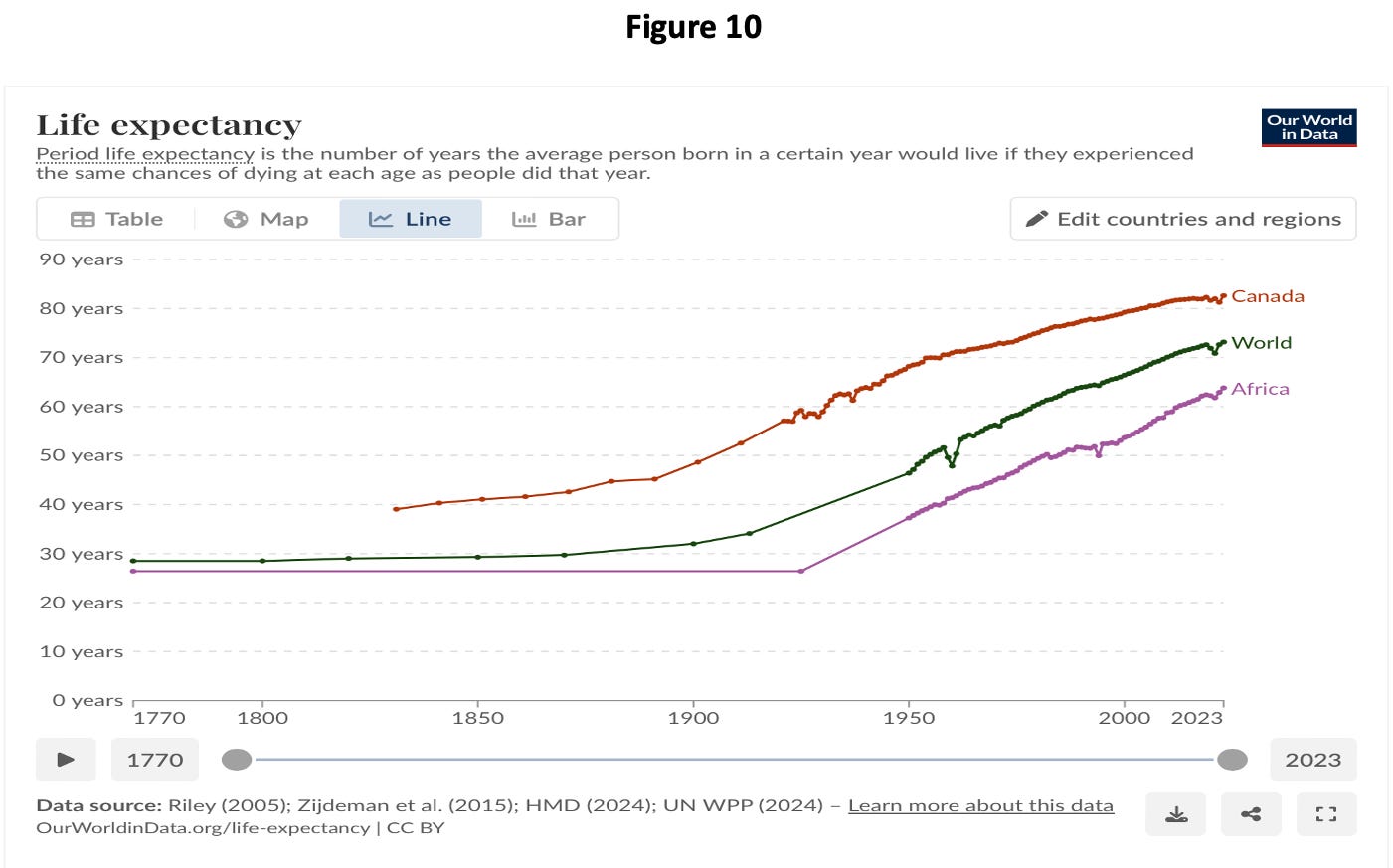

Steady increases in GDP per capita over 200 years, increasingly spread throughout the world, albeit unevenly, would seem to be self-evidently a good thing. But there has always been a current amongst the chattering classes that has decried modernity. Its most recent manifestation is the “Degrowth Movement.” Figures 7-10 below provide a small slice of what economic growth has meant in terms of human wellbeing, both in “rich” countries, and in “developing countries.”

Was it overwrought to suggest at the start of this post that energy illiteracy could kill us?

Progress is not inevitable. History is replete with examples of things coming undone when due care and attention is not paid to maintaining the system that was generating progress. Indeed, the overall theme of Blindingly Obvious is that Canada has not been tending properly to its progress machine.

As this post has shown, a critical part of that progress machine is an energy system that augments the muscle and brain powers of Canadians. That system must supply inexpensive, reliable energy in the right form, at the right place, at the right time. Understanding this is the essence of what is meant by energy literacy.

I wish I could see more evidence that the Canada’s policy approach to the energy transition is well-informed by energy literacy. If energy policy is not energy literate, we could start to go backwards, and the progress that we have already made could start to unravel. Look back at Figures 7-10 and decide for yourself if you think the start of this post was overwrought.

In the next few posts, I plan to lay out some basic lessons in energy literacy. There will be nothing profoundly original in this. In fact, it will be all consistent with the brand name of this Substack. But, as Mr. Orwell reminded us, sometimes it takes a bit of a struggle to see things in the front of your nose.

[1] See, for example, https://nationalpost.com/news/canada/top-carney-adviser-wanted-list-of-oil-and-gas-cap-off-ramps-in-2023-documents-show .

[2] https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/2025-02/Canada%27s%202035%20Nationally%20Determined%20Contribution_ENc.pdf

[3] For a good discussion of the Malthusian Trap, see https://ourworldindata.org/breaking-the-malthusian-trap

[4] Wind power was utilized to a limited extent – most significantly to provide the motive power for shipping by sea. But this did not change the fundamental constraint imposed by the thin margins on human and animal work. Anybody interested in exploring all of this in more detail should delve into the work of Vaclav Smil, in particular, Energy and Civilization and How the World Really Works.

[5] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Energy_slave

Ah, I was saying to myself as I read, this guy reads Vaclav Smil! And then I saw your footnote to his work. Makes good sense. It's funny to me, as I've tried to read more economics, about how little is said about how the availability of cheap (transportable, storable) energy is fundamental to technological development. I read about monetary theory, interest rates, etc., but very little about how it all depends on hugely dense energy from the sun.

I'm also looking forward to the next in the series. In my layman's understanding, we're using far too little nuclear power given how clean and relatively (much) safer it is than burning coal and other fossil fuels. I don't get the resistance to it by governments.

And as a renting millennial with no home (and so no home equity) to inherit, it's great to have you in the corner younger Canadians. Reassuring someone like yourself was at a high level of our government, I always wonder just how deeply those at that level think about issues, vs the issues of the day. And we need some serious reform to the benefits older Canadians get. It's so wasteful to be transferring wealth in the form of full OAS benefits from working Canadians to seniors with incomes of 90k a year. That's a full $25k more than the median Canadian salary! And they have the lowest poverty rates.

An excellent analysis. I'm looking forward to the next one in this series.