We Can Have Our Own Values, But We Can’t Have Our Own Arithmetic

Some Thoughts on How to Unwind the Ponzi Problem

In the last three posts we have been talking about the Ponzi Problem arising from the establishment in the 1960s and 1970s of what we labelled Canada’s Senior Promise. We showed that there was an inherent problem baked in from the beginning,[1] that the idea that we could solve the problem through aggressive increases in immigration levels is bogus,[2] and that the burden of maintaining the Senior Promise up until now has been borne almost exclusively by younger Canadians.[3]

In this post we will turn to talk about how we can solve the Ponzi Problem.

Selection Criteria

Four complementary actions that Canada should take to resolve the Ponzi Problem will be sketched out below. Before doing so, however, it may be helpful to lay out the criteria used in choosing these four actions. The choices are guided by three principles, sometimes in tension with each other:

Principle 1: To the extent feasible, we should choose actions that do not adversely impact any particular generation.

Principle 2: All generations should contribute to the solution. It is not acceptable to continue to expect that all of the burden should be borne by younger Canadians.

Principle 3: Any changes to the terms of the Senior Promise should be introduced gradually, so that people can modify their plans for retirement well in advance.

Four Actions to Fix the Ponzi Problem

1. Restart the Progress Machine

A constant theme of Blindingly Obvious has been the failure of public policy to focus on maintaining the conditions that lead to steady, year-over-year improvements in the standard of living of the broad middle class. Wages rising at 2 ½ percent a year over the rate of inflation means a doubling every 28 years. Canada had this in the 30 years after World War II, and it is not unreasonable to think it can be achieved again.

But in order to achieve this again, Canadian policy makers need to return their focus on creating the conditions that will facilitate this happening:

A labour market tight enough to motivate businesses to invest in improving productivity and to share the gains of those productivity improvements with workers. In particular, policy makers have to put an end to the cheap labour strategy[4]

Paying attention to the basic arithmetic of Canada’s standard of living in choosing which industries to encourage (as opposed to discourage);[5]

Paying attention to Canada’s “gravity problem” and ensuring that public investments in creating intangible assets enhance Canadians’ standard of living on an ongoing basis;[6]

Recognizing that housing affordability requires policy makers to pay attention to demand as well as supply.[7]

If Canada can return to an economy where there is steady year-over year increase in real wages, the burden on the working population of supporting the Senior Promise becomes much less onerous. The Old Age Security (OAS) and Guaranteed Income Supplement Plans are indexed to the rate of inflation. If wages rise each year by, say 2 ½ percent, over the rate of inflation, the burden of paying for this part of the Senior Promise will be reduced, even as the Old Age Dependency Ratio rises.

2. Reform Our Health Care System

Our proximity to the U.S. has made our thinking on health care quite lazy. We think that, just because our system appears more equitable than that south of the border, we have a great system. The sad reality is that, in comparison to systems elsewhere in the world, our system is not that great. I hope to have a more detailed dive on this in a future post, but in the meantime the keen reader might want to check out the most recent Commonwealth Fund review of health care systems.[8]

As our senior population grows, throwing more money at the system cannot be the only policy choice. The performance of other countries suggests that it is possible to get better outcomes relative to the public funding provided. Reform of the health care system should be a key part of responding to our challenge.

As a side benefit, a reformed system could provide better results for the non-senior segment of the population.

3. A Tighter Needs-Based Lens on Senior Programs

Every year when my wife and I submit our income tax returns we are able to split our pension income and also receive an additional tax credit on that pension income. Last year that reduced our joint tax bill by more than $5000. Why? Are our expenses more than, say, those of our neighbours, who are paying off their mortgage and have two school age children? Nope. The simple truth is we get that tax break simply because we are pensioners.

But wait, there’s more! Full OAS payments (approximately $8800/year for those 65-74, $9700/year for those 75 or older) are available to individuals with annual income less than $90,000. While there is a “clawback” over that income level, some OAS payments are available to individuals with an annual income up to almost $150,000. Both members of a couple are eligible to receive OAS payments, but the eligibility is based on individual income, not on the couple’s total income, so potentially a couple could get the full OAS payment even if their joint income was $180,000, and would receive some benefit up to a joint income of almost $300,000.

The original rationale for OAS was, indeed, security – it was intended to support seniors who had limited sources of other income. In 2023 it cost the federal government $60 billion, and is projected to cost $106 billion by 2035.[9]

But wait, there’s more! There is an income tax credit for anyone 65 or older with an annual income less than $103,000.

But wait, there’s more! … Well, the basic point should be clear by now: elements of the Senior Promise that were originally conceived in terms of providing old age security seemed to have morphed, campaign promise by campaign promise, into a set of entitlements which are hard to justify with a needs/equity lens.

Given the unfair burden borne by younger Canadians in supporting the Senior Promise, isn’t it time we started asking Boomers to shoulder some of the burden?

The preferential income tax treatment for seniors – the deduction for pension income, the ability of couples to split pension income, and the age tax credit – should be phased out. A childless couple in their 70s should pay the same income tax as a childless couple in their 30s with the same income. Why would we think otherwise?

The eligibility for OAS payments should be tightened up, so that this benefit starts to taper off at a lower income level - $90,000 is well above the average and median income levels of any age group.[10]

4. Gradually Raise the Retirement Age

As pointed out in previous posts, life expectancy at 65 has increased significantly since the 1960s, when the terms of the Senior Promise were crafted. In 1965 a 65-year-old could expect to live another 15 years; by 2024, that had grown to 21 years.

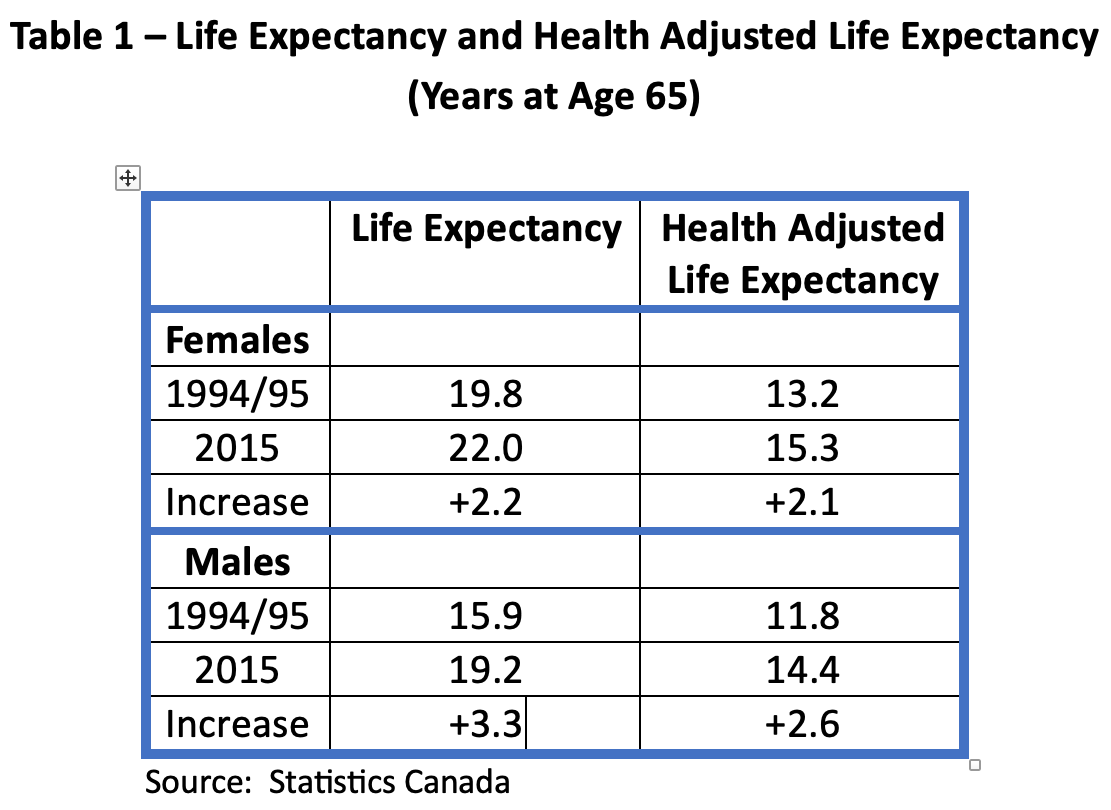

Not only are Canadian workers living longer, but they are also staying healthier longer. The shop-worn notion of a senior as a frail old person in a rocking chair is long past its best-by date. Statistics Canada periodically estimates a “Health Adjusted Life Expectancy” (HALE). HALE represents the number of years of life lived in good health that could be expected, based on the average experience in a population if current patterns of mortality and health states persisted. Table 1 below shows how Life Expectancy and HALE have increased over the 1994/95-2015 period.

Note that the increase in HALE is 80-95% of the increase in life expectancy between 1994/95 and 2015. The source for Table 1 is the most recent, consistent estimate of HALE that I could locate.[11] There is no reason to believe that the correlation between the increase in life expectancy and HALE began only in 1994/95 and ended in 2015.

The increase in life expectancy had obvious implications for the affordability of the Senior Promise - in the absence of any increase in the retirement age the Senior Promise becomes significantly more expensive. The extension in the length of healthy lives, on the other hand, provided an obvious solution, at least in part, to this – pushing out the normal retirement age.

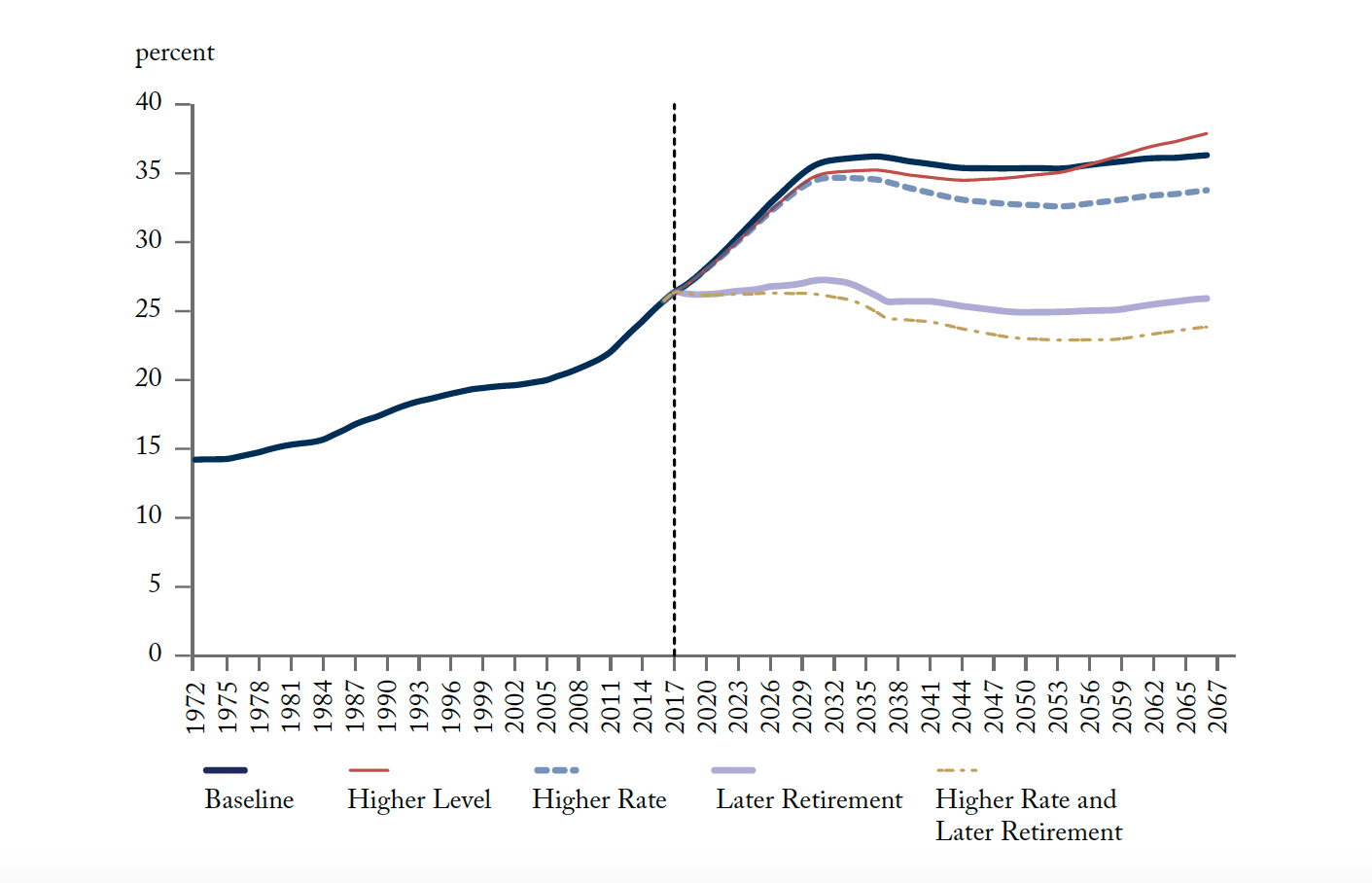

We had previously referred to a study by Robson and Mahboubi (R&M)[12] which simulated the Old Age Dependency Ratio (OADR) under different immigration scenarios. R&M also ran scenarios in which the retirement age was extended. The specific scenario was one where the retirement age would rise by three months every year over a twenty-year period, rising from 65 to 70.

Figure 1 below is from R&M. It shows what happens to the OADR under their different scenarios. The Baseline line traces the scenario where immigration rates followed those from the years before the Justin Trudeau government. The Higher Rate line traces the scenario where immigration rates followed the higher rates articulated in the first term of the Trudeau government. The Later Retirement traces out the scenario where the retirement age is extended out as explained above.

Figure 1 - Actual and Projected Old Age Dependency Ratio: 1972-2067

Source: Robson and Mahboubi

The first post in this series on the Ponzi Problem made the point that increasing the rate of immigration only mitigates to a minor degree the increases in the OADR – as reflected here by the minor difference between the Baseline and the Higher Rate Line in Figure 1. The Later Retirement line, on the other hand, is starkly different – the OADR flattens out, and ends up slightly lower than in the base year of 2017. Pushing out the retirement age to fully reflect the increase in healthy life expectancy since the 1960s would essentially solve the Ponzi Problem.

This type of approach has been adopted in other countries similar to Canada. For example, Denmark has a current retirement age of 67, but has recently legislated an increase to 68 in 2030, to 69 in 2035 and to 70 in 2040.

The Stephen Harper government announced a step in this direction in its 2012 budget. The age of eligibility for the full OAS payments would be extended by three months each year, starting in 2023 until it reached 67 in 2029 – providing a reasonable period of time for people to plan their approach to retirement.

After being elected in 2015 the Trudeau government delivered on its commitment to reverse the Harper change. In its platform for the recent election, the current government reconfirmed this commitment:

“We have always stood up for seniors. The previous Conservative government, which Pierre Poillievre was part of, tried to raise the age of retirement to 67. Liberals reversed this to protect Canada’s promise that, after a lifetime of hard work, senior deserve a safe and dignified retirement.”

Values Versus Arithmetic

Any long-term solution to the Ponzi Problem will require some combination of the four actions listed above. There will obviously be political challenges with each, particularly with the last two. This post is already on the long side, so an extensive discussion of these challenges will be deferred for now.

As the quote from the Liberal platform makes clear, the resistance to measures that would put the Senior Promise on a more sustainable basis will be couched in very value-laden language.

I have advised governments that I have served in the past that they could have their own values, but they can’t have their own arithmetic. Claiming that significant changes to the terms of the Senior Promise are not necessary indicates, I regret to say, a pretense that Canada can, indeed have its own arithmetic.

[1] https://donwright.substack.com/p/how-did-canadas-senior-promise-turn?r=78jix

[2] https://donwright.substack.com/p/the-bogus-idea-that-will-not-die?r=78jix

[3] https://donwright.substack.com/p/hey-boomers-lets-do-the-right-thing

[4] https://donwright.substack.com/p/too-little-invisible-hand-too-much?r=78jix

[5] https://donwright.substack.com/p/the-basic-arithmetic-of-canadas-standard?r=78jix

[6] https://substack.com/home/post/p-167828895

https://substack.com/home/post/p-168442683

https://substack.com/home/post/p-169479167

[7] https://donwright.substack.com/p/how-did-the-wheels-fall-off-the-progress?r=78jix

[8] https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/fund-reports/2024/sep/mirror-mirror-2024

The Commonwealth Fund’s primary focus is on the failings of the U.S. health care system, but it regularly compares the U.S. system to those of other rich countries. If one looks past how they rate the U.S. system, it will become clear that Canada is not exactly at the top of the class.

[9] https://www.osfi-bsif.gc.ca/en/oca/actuarial-reports/actuarial-report-18th-old-age-security-program-31-december-2021#

[10] See the work done by Generation Squeeze for a more in depth look at the tax breaks that seniors currently receive.

https://www.gensqueeze.ca/recommendations_for_the_carney_governments_first_budget

[11] https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/82-003-x/2018004/article/54950-eng.htm

[12] https://cdhowe.org/publication/inflated-expectations-more-immigrants-cant-solve-canadas-aging-problem-their-own/

No issue with many of your points and redressing the balance (we also benefit from some of these like income splitting). On the retirement age question, for those of us white collar professionals, makes sense but I sometimes wonder should there not be some differentiation between people like us and “manual” workers whose bodies experience more wear and tear. Would be hard to administer however.

Letting OAS erode relative to wages (compared to a history of ad hoc increases despite the formal indexing) doesn’t fix the fairness issue, even if it fixes the budget issue. This is still young people paying most to solve the problem, contributing just as much of their income now for a less generous benefit later. (In fact, the only real appeal of pay as you go programs is that if wage growth is high benefits that keep up with wages may very well beat private saving, at least in lower-risk investments).

You might hope wage growth would be reasonable compensation to today’s young, but so many big costs (say housing, or labour-intensive services) are about what you make relative to other people. This is half the reason the ad hoc increases to benefits exist in the first place. You can only grow your way out of the entitlement problem if we’re willing to let seniors lose ground relative to young people (which has absolute consequences in some aspects of standard of living). Particularly for GIS, it’s hard to see a world in which wages double and the floor for seniors stays the same.