Travel Notes – Japan

What Does a Country Do When It Realizes That Its Self-Satisfied Contentment is Not Justified?

In my last post I wrote about a visit to Iceland in June and the lessons for Canada I found there.[1] This post will be about Japan.

We try to get to Japan at least once a year. Visiting grandchildren is a great motivator.

While the primary draw of Japan is our son and his family, Japan itself is a wonderful country to visit. The food is amazing.[2] Virtually everything is high quality, with exquisite attention to detail. It is very safe and clean. Our (still quite young) grandchildren travel about Tokyo on their own – walking, biking, by bus or by train – and their parents do not worry in the least about them. Tokyo has the amenities of a big city, but feels like a conglomeration of small towns where everything you would want day-to-day is close by in pleasant, walkable neighbourhoods.

And there is plenty to see outside Tokyo as well. Every time we go there, our son arranges a small mini vacation to a part of Japan we haven’t seen before. This year he arranged a quick trip to Kagoshima Prefecture at the south end of Kyushu, the southernmost island of the four main islands of Japan. This prefecture includes Satsuma, an old province that is shown in red in the map below.

One day we visited a museum that focused on the important role that Satsuma played in the modernization of Japan. This was a story I was not aware of before this visit. As I reflected on it, it seemed to me that there are some lessons for Canada in that story. To get to those lessons, however, we first need to go through a bit of potted Japanese history.

The Tokugawa Shogunate and the Isolation of Japan

After almost continual civil war between 1454-1603, Japan was ruled by the Tokugawa Shogunate. While the position of Shogun was passed down from generation to generation within the Tokugawa clan, the Shogun was not the Emperor. The position of Emperor was still held within the Imperial family, but his power was completely nominal – he was a figurehead and not much more.

The Shogunate was a feudal system – Japan was divided up into approximately 270 hans (domains) each ruled by a daimyo (lord). Each daimyo had significant autonomy over his han, but had to pay an annual tax to the Shogun, and to abide by strict rules – mostly designed to prevent any daimyo becoming strong enough to challenge the Shogun, and lead to another outbreak of civil war.

One of the rules laid down was a strict ban on anyone leaving Japan, and on foreigners entering Japan, with some very strictly regulated exceptions. The reason for this decree was to prevent outside influences,[3]resources or technologies from upsetting the power balance established by the Tokugawa.

For 250 years, the Shogunate seemed to work. The constant civil wars were put to an end. Fewer resources needed to be devoted to military expenditures, and the ensuing peace allowed commerce to recover and flourish. The isolation from the rest of the world was not just accepted, there was a sense of self-satisfied contentment – Japan could get along just fine without interacting with foreigners – and this would allow Japan to maintain its sovereignty.

But this isolation also had a time bomb built into it. Japan was oblivious to how world trading patterns had changed during the age of European exploration. Even more significantly, it was unaware of the energy/industrial revolution that occurred in Europe and the United States from the late 1700s through the mid 1800s.

So, when the Americans and Europeans started showing up on the shores of Japan, there was a very significant power imbalance because of the difference in technological capabilities. U.S. Navy Commander Perry showed up in Tokyo Bay in 1853, and not so subtly suggested to the Shogunate that Japan would open up to the outside world. A number of one-sided “friendship agreements” with the Americans and Europeans were the result.

Satsuma’s Particular Role in Japan’s Response

The daimyo of Satsuma at this time was Shimazu Nariakira. He quickly recognized how much of a threat the European and American advanced technologies represented to Japanese sovereignty, and initiated educational reforms, and adopted western technologies to the extent feasible in his domain.

He understood that this would not be enough. He concluded that Japan needed to, on a very accelerated basis, go out into the world and learn about all the technological advances that had occurred since the 1600s, learn about how the European societies had developed the capabilities to generate those technologies, and develop the mechanisms to apply those technologies and capabilities at scale in Japan.

After 250 years the Tokugawa Shogunate had entered the decadent stage. Its response to the foreigners was quite feeble. In particular, it seemed unwilling or incapable of organizing the type of response that Nariakira believed was necessary.

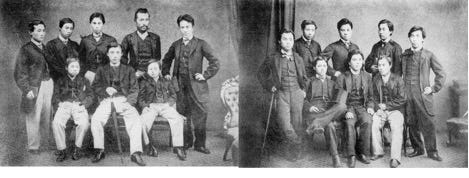

Nariakira died in 1858, but his successor pursued the same drive for modernization. Out of frustration from the inaction of the Shogunate, he commissioned a “learning mission” to Europe in 1865. Nineteen of its young “best and the brightest” were sent to London to study at University College. Some of them also supplemented this by going to other parts of Europe. The two pictures below show sixteen of the Satsuma students in their “western-style dress.”

Keep in mind that the prohibition on leaving Japan was still in place. Thus Satsuma was acting in defiance of the Shogunate. The punishment for violating the prohibition was death. So, this was a not inconsequential step to take.

Eighteen of the Satsuma students returned to Japan and played major roles in the modernization of Japan.[4]

The Meiji Restoration

In 1866 Satsuma formed an alliance with another domain, Chōshū, to overthrow the Tokugawa Shogunate, and restore Imperial rule. This rebellion was successful, and in January 1868 the Shogunate was abolished in what has been called the Meiji Restoration. The Emperor returned to a more substantial role. But it is important to understand that the Imperial family was as much a convenient vehicle for the modernization of Japan as it was the driver of this process. The drivers of the process were those elites who wanted Japan to modernize, and catch up with the Europeans and Americans.

While the group of nineteen Satsuma students were the first to go abroad to vacuum up as much as they could about the technologies, and the creation of the capabilities to generate new technologies, they were by no means the last. One of the first actions of the new government was to send out the Iwakura Mission in 1871-73, consisting of more than 100 officials, scholars and students to the U.S. and Europe to study Western politics, industry, education and military strategy. Their learnings were brought back and informed the modernization of Japan.

And What Were the Results of All of This Learning?

At the time of the Meiji restoration, the leading industrial country – the country with the highest GDP per capita in the world - was Great Britain. In 1869 Japan’s GDP per capita was only 27 percent of that of Britain. Over the next 70 years Japan did not fully eliminate this gap, but its per capita GDP grew by 204 percent compared to 71 percent for Britain.

Japan fought on the side of the Allies in World War I. The 1920s and 1930s were not a great period for liberal democracies across the world, and Japan was one of the countries that took a dark, ultra-nationalistic turn, which ultimately led to the Pacific theatre of World War II and Japan’s devastating defeat in 1945.

After the war, Japan rebuilt itself as an economically and socially successful democracy. In that process the Japanese demonstrated some of the same willingness to learn from the rest of the world after 1945 as they had in the nineteenth century. Most notably, Japanese manufacturers took on board William Deming’s Total Quality Management approach, and by the 1980s had become the most successful manufacturing nation in the world.

Japan subsequently lost some of that manufacturing edge as other Asian “tigers” – South Korea, Taiwan and then China followed a similar path. But Japan remains a high-income, socially stable country.

Are There Lessons for Canada Here?

There is an obvious parallel between the situation facing Japan in the 1850s and the situation facing Canada now. The rules of engagement with the outside world have changed, and this poses a real threat to our standard of living and sovereignty. Just like the Japanese then, we realize that our self-satisfied contentment is not justified. We need to be prepared to take new and uncomfortable paths in order to maintain our sovereignty.[5]

But there is also a more general lesson here – about our willingness to actively learn from what other countries have done/are doing.

We like to flatter ourselves that we are an internationally minded people, and therefore open to ideas from everywhere. But are we really? I honestly cannot think of any Canadian example that comes remotely close to the learning exercises that the Japanese undertook in the aftermath of Commander Perry’s mission to Tokyo, or in the aftermath of their defeat in World War II. Even on a very narrow subject, let alone as a whole-of-society exercise.

Perhaps the root of our problem is our obsession with our big neighbour to the south. We seem to be caught in a vortex of competing urges to be just like the Americans on the one hand, and to be the opposite of the Americans on the other hand. That seems to stunt our ability to forget about the Americans, at least for a while, and go out and look at how other jurisdictions solve their problems.

In his recent excellent book recent book or immigration,[6] Tony Keller captured this well:

“But living next to the colossus that is United States can make Canadians very parochial. We gaze at our navel, and at theirs, and sometimes have trouble seeing further.”

One blatant example of this is our thinking about health care. We have trapped ourselves into defending a model of delivery, that is clearly in need of reform, simply because it is not the American approach. But there are other models around the world that deal more effectively with the equitable access issue and deliver better service results. Isn’t it long past time that we did a Japanese-like learning exercise on health care?

Or perhaps we could learn how the Finns maintained their independence and freedom to operate in the years after World War II, despite the fact they lived right next to a much larger, more powerful, and not particularly benign, superpower.

I am sure you could list a number of other areas where Canada could benefit from learning more about how other countries deal with their issues.

Let’s leave it there for now.

[1] https://donwright.substack.com/p/travel-notes-iceland?r=78jix

[2] And not just Japanese food. I have heard some hard-core foodies state that they have had their best French food in Japan. My own experience has turned up nothing to contradict that.

[3] The Shogunate had a particular concern about the spread of Christianity – it saw Roman Catholic missionaries as a threat to its authority, fearing they could undermine the Shogunate’s control and become a tool for foreign powers.

[4] The one who didn’t return was Nagasawa Kanae. He is the young student on the right end of the first row in the photograph on the left. He was only thirteen when they sailed for Britain. He ended up going to California where he became that state’s largest wine producer and is credited with introducing California wines to the international world, particularly to Europe. He has been described as the “Robert Mondavi of his time.”

[5] Let’s hope, however, that we can find that path without an actual insurrection against the existing government.

[6] “Borderline Chaos. How Canada Got Immigration Right and then Wrong.”

I was also recently in Japan, as I’ve read many times, they seem to be healthier than North Americans. The food environment likely plays a large role, we know that it’s largely what drives the overconsumption in NA — easily available highly processed high calorie foods. That said, their medical costs per capita are about the same as ours, though they likely have an older population already.

Speaking as a policy analyst, I rarely look to the USA for inspiration, usually it’s other commonwealths, Britain, and some of the European countries. I admit not looking to Japan.

Glad to hear you’re enjoying Keller’s book, an excerpt was published in the G&M while I was in Japan, fantastic reading, and I’m looking forward to the book.

Thanks very much, Don, for writing this blog. It is a very interesting tale you tell, highlighting the current shortcomings of Canada, and of our inability to examine our own failings, and to function effectively as a modern society.

The contrast between our current myopia and ineffectiveness today and our extraordinary performance in WW II, with a population of only a little over 10 million people is astonishing.

There are many explanations of why this has occurred, but one significant contributor has been the abysmal failure of our educational system, schools and universities alike, to teach young people and newcomers of the extraordinary vision, drive, and tenacity shown by leaders and citizens alike, from the early days of settlement and colonization, to build a Country that became one of the leading examples in the world of what a free, democratic society can accomplish when it tries.

Today, as a Post National country, in Justin Trudeau’s view, we have become a guilt-driven, apologetic society, depending on the United Nations to define how we should behave and what our goals should be.

What a sad, sorry, and foolish society we have become.

Ken Wilson