The Bogus Idea That Will Not Die

The Population Growth Advocates Keep Pushing a Ponzi Scheme

“A Ponzi scheme is an investment fraud that pays existing investors with funds collected from new investors. Ponzi scheme organizers often promise to invest your money and generate high returns with little or no risk. But in many Ponzi schemes, the fraudsters do not invest the money. Instead, they use it to pay those who invested earlier and may keep some for themselves.

With little or no legitimate earnings, Ponzi schemes require a constant flow of new money to survive. When it becomes hard to recruit new investors, or when large numbers of existing investors cash out, these schemes tend to collapse.”

United States Securities and Exchange Commission

In the nine years 2016-24, the Justin Trudeau government granted permanent resident status to 3.2 million new Canadians and presided over a net increase in non-permanent residents of 2.2 million. The resulting 5.4 million increase in Canada’s population was more than twice what it was in the previous nine years. Even prior to 2016 Canada had a higher proportion of its population born in other countries than any of the other G-7 countries.

I have made no secret of my belief that the immigration policy of the Trudeau government was the single most significant Canadian public policy blunder since at least the 1930s.[1] The largely unplanned surge in population contributed to, inter alia:

· Weakened workers’ bargaining power with employers, particularly for lower-paid workers;

· The resulting “cheap labour strategy” lessened the incentive for business to innovate and invest in productivity improvements;

· Younger Canadians finding it more difficult to get summer employment or that first significant job;

· Canada having the 3rd worst growth in GDP per capita of 38 OECD countries since 2015;

· More fuel on the fire of our housing crisis;

· Further stress on our already overloaded health care, education and social services systems; and

· Further stress on inadequate transportation infrastructure across the country.

But perhaps the greatest damage done was intangible – the decades-long public support for healthy levels of immigration has been reversed. Environics has been surveying Canadians attitudes to immigration since 1977. From 2000 to 2022 a healthy majority of Canadians disagreed with the statement, “Overall there is too much immigration in Canada.” In its most recent survey in September of 2024, 58 percent of Canadians agreed with that statement, as opposed to only 36 percent who disagreed. Sadly, Canadians’ dissatisfaction with immigration policy has led to a more negative view of immigrants. For example, 57 percent of Canadians agree with the statement, “Too many immigrants do not adopt Canadians values.”[2]

Mere Negligence?

While it would be comforting, in a perverse sort of way, to explain this blunder as mere negligence on the part of the Trudeau administration, I am afraid there are doctrinal elements to it as well.

The one that I have stressed in previous posts is the curious attachment to the “shortage of workers” narrative – aka the cheap labour strategy. Let me repeat what I have said before – there was never a shortage of workers, but rather a shortage of employers willing to pay the wages that Canadian workers expected.

The doctrinal element that I will discuss today is the argument that Canada needs to grow its population significantly beyond its current level over the balance of this century. This argument is explicitly promoted by an organization called The Century Initiative, whose founders and board members over the years have been prominent business and political leaders.[3] Some of these leaders played a prominent role in the Advisory Council on Economic Growth set up in the first term of the Trudeau government. A core recommendation of that body was to ramp up Canadian immigration levels significantly – to 450,000 by 2021 (in 2015 the number of people granted permanent resident status was 272,000) - a recommendation the government began to act on immediately.

The larger population was somehow supposed to make Canada a more successful country – though the criteria for measuring success was always somewhat hazy. A bit of handwaving about larger domestic markets, economies of scale, agglomeration economies, greater international influence and the like. Perhaps in a subsequent post I will take a look in more detail at those arguments.[4] In this post, however, I want to focus on one particular argument that has always been put front and centre.

The Bogus Idea That Will Not Die

The most frequently cited argument in favour of high immigration is that it is essential in order to deal with Canada’s aging population.

The essence of this argument is that, as the last of the Boomers retire over the next few years, the ratio of seniors to the working age population will rise. Seniors place higher demands on the public purse to pay for their income support, health care and subsidized long-term care. If the proportion of the population of working age shrinks, these higher costs will have to be paid by a relatively smaller taxpayer base. The only remedy for this is to ramp up immigration levels.

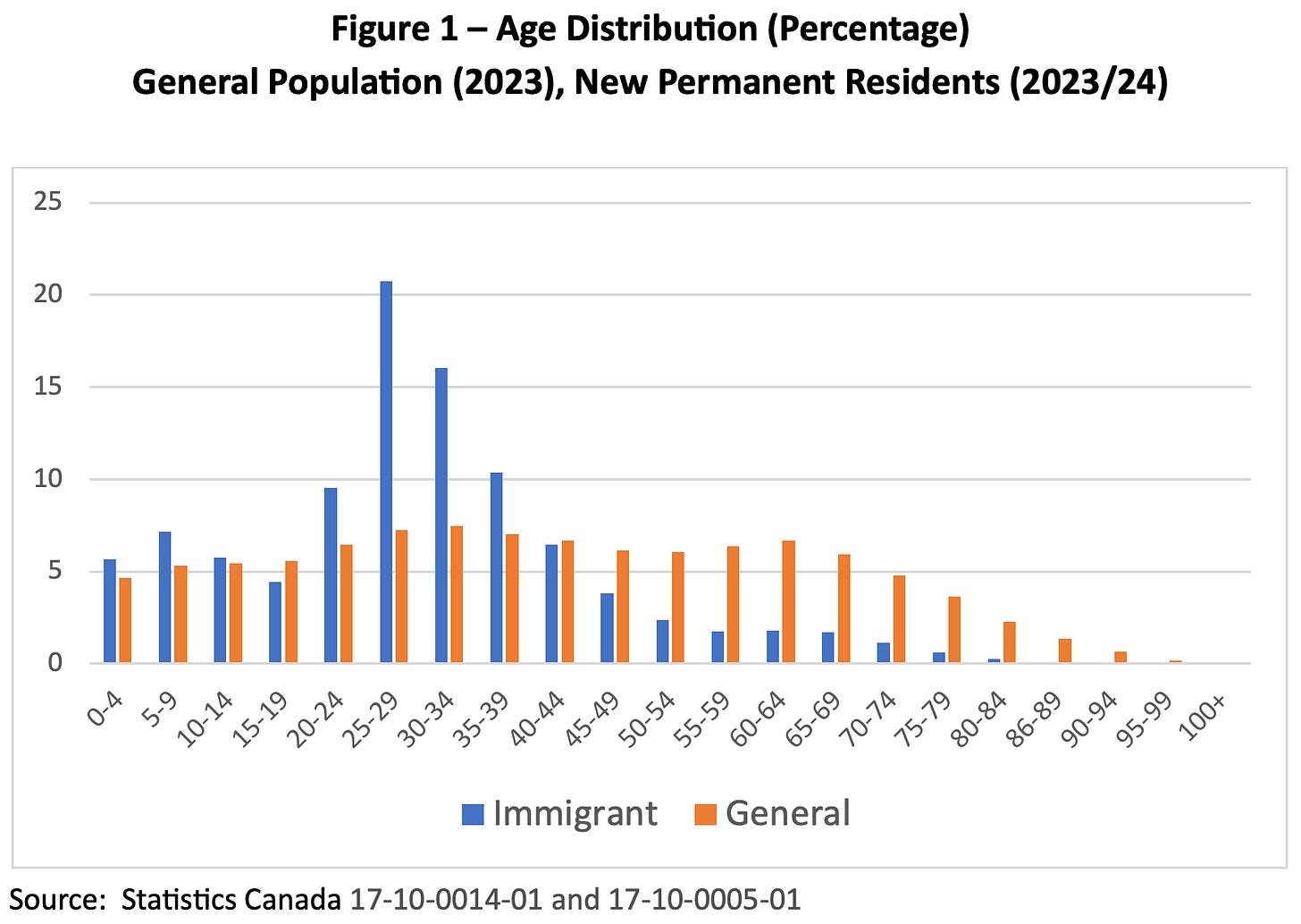

At a superficial level, this argument seems plausible, which is why it is accepted almost as an article of faith. It is true that the age distribution of immigrants skews younger – on average by approximately eleven years - than that of the general population, as shown in Figure 1 below.

But the argument is only superficially plausible. People don’t stay young forever. Immigrants of working age who arrive in Canada today will, in time, also reach retirement age. They then add to the public purse challenge of supporting seniors.[5]

To determine whether the argument is valid that higher immigration is the solution for the boomers, we need to look past a snapshot at one point in time and look at how Canada’s age structure would evolve through time. A CD Howe Institute study by Robson and Mahboubi (R&M) in 2018 did exactly that.[6] In that study R&M did a number of simulations between 2017 and 2067 testing different assumptions about immigration levels and retirement ages. One of the key indicators they tracked in these simulations was what happens to the Old-Age Dependency (OAD) ratio – the ratio of the past-the-retirement-age population to the working-age population. In 2007 this ratio was 20.5 percent.

R&M developed a baseline scenario in which immigration levels continued at the pre-Trudeau percent of population. Another scenario had immigration rise at the rate recommended by the Advisory Council on Economic Growth. By 2067 the OAD ratio in the baseline scenario rose to 36.3 percent; under the higher immigration scenario it rose to 33.8 percent. So, the higher immigration scenario does mitigate the aging problem slightly. But only slightly – it does not fix the fundamental problem. As R&M explain:

“The limited effects of immigration on demographic structure are different from what many people imagine, so it is worth emphasizing that the momentum of aging in the already-resident population – and in each cohort of immigrants as they too age – is very hard for immigration to counteract.”

To further emphasize this point R&M calculated the levels of immigration required to stabilize the OAD ratio. They calculate that immigration levels would have to rise to such a level that Canada’s population in 2067 would be 156.2 million – 4.26 times its 2017 level. R&M wryly observe:

“That preposterous scenario illustrates a sensible point: hopes that immigration can offset demographic aging in Canada do not survive an encounter with the numbers.”

And yet, those hopes – generally stated as an urgent necessity - continue to be voiced by governments and the commentariat.

Why won’t the bogus idea that higher immigration is the solution to the aging boomer problem die?

It’s Not a Demographic Problem, it’s a Ponzi Problem

The reason the bogus idea won’t die is that there has been a consistent misdiagnosis of the basic problem. Those who argue for higher immigration implicitly assume that the problem arises from the fact that the generations after the Baby Boom were smaller than it – and that the purpose of the higher immigration levels is to make up for that. But that is not the real problem.

The real problem arises from the terms of what might be called the “senior promise.” This is the guarantee that the government funding to provide old age security and other income support programs, high quality health care and subsidized long-term care, will always be there, paid for by the currently working generations. This in turn was premised on younger generations being substantially larger than the currently retired generation. There was a further implicit assumption involved – that seniors would continue to live the same number of years after reaching retirement age.

The senior promise was established in the 1960s and 1970s, when the younger generations were significantly larger than the retired population. That proportion no longer exists. Furthermore, in the 1960s a person reaching the age of 65 could expect to live another 15 years; by 2023 that had been extended to 21 years.

There has been essentially no revision of the terms of the senior promise since it was established 50-60 years ago, and the result is that the only way it can be fulfilled is if each generation is significantly higher – not just the same size – as the generation preceding it. R&M showed that required an increase in population by 4.25 times over fifty years. But that more than quadrupling would have to continue every fifty years – by 2117, Canada’s population would need to be in the neighbourhood of 665 million.

What we are describing is essentially a Ponzi scheme. All Ponzi schemes ultimately collapse when it becomes impossible to recruit enough new “investors” to keep the scheme going. The longer it goes on, the bigger the eventual collapse. You can’t fix a Ponzi scheme by keeping it going.

And yet, that is essentially what the proponents of greater population growth are offering as the solution – their advice is to keep the Ponzi scheme going.

In the next few posts, we will look at this in a little more detail – how the terms of the senior promise arose, what we can do to make it sustainable going forward, and the intergenerational consequences if we instead keep the Ponzi scheme going.

[1] See, for example, previous Blindingly Obvious posts: https://donwright.substack.com/p/how-did-the-wheels-fall-off-the-progress?r=78jix

and, https://donwright.substack.com/p/too-little-invisible-hand-too-much-767?r=78jix

[2] https://www.environicsinstitute.org/docs/default-source/default-document-library/final-report94fae631-0284-4ba5-b06a-e0aeeab5daf3.pdf?sfvrsn=9f47b717_1

https://www.centuryinitiative.ca

In the interest of full transparency, I should point out that I participate on an advisory committee set up by the Century Initiative. To her credit, the CEO invited me to sit on this committee knowing my opinions on immigration policy did not exactly align with those of the Century Initiative.

[4] In the meantime, the keen reader can check out: https://clef.uwaterloo.ca/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/CLEF-058-2023.pdf

I also touched on some of this in the section “Some nuance on immigration, please (It’s GDP per capita stupid!)” in https://ppforum.ca/publications/don-wright-middle-class/

[5] In the first version of this post, I mentioned that the number of senior and soon-to-be senior immigrants is likely to rise over time, as the political pressure to raise the number of parents and grandparents of immigrants admitted to join their families in Canada will continue to rise. After reading a number of comments on that post, I realized that this point was a distraction from the more important point that immigrants age, and accordingly have taken it out in the version now posted. The reader interested in delving further into this issue can see my reply to those comments.

[6] See https://cdhowe.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/March-9-e-brief_274-Web.pdf

My general “policy” is to not respond to comments – let’s just let the discussion and debate happen. With this post, however, there was a particularly diverse set of comments that made some interesting suggestions and posed some interesting questions. So, I thought it would be useful for me to provide some brief responses.

Andrew Roman:

Agree with the comment about how raising the retirement age could be an important part of the solution. Stay tuned.

Marnie Wright:

When will the probable end occur? What I am hoping is that we will agree to make the changes that will make the senior promise sustainable over time. Part of the solution will be, in my opinion, a gradual increase in the retirement age, as just noted in my response to Andrew Roman. But I don’t believe that will happen within your retirement planning horizon.

Stephen Hureau, Tom Stringham and Andrew Griffith:

Thank you. Tom, you may also be interested in my response to Segmentation Fault and CupOfSoup

Chris:

Agree that other “Western” nations are facing Mr. Ponzi as well. Your comment about politicians giving Mr. Ponzi another try every 4 years does underline the main political challenge - the temptation is to always kick the can down the road. At the risk of sounding naïve, I hope that, with proper public discussion, some corrective measures to make our senior promise sustainable will be taken. As a positive example, which I will discuss in a future post, I would point to Paul Martin’s fix of the Canada Pension Plan in the late 1990s.

Segmentation Fault and CupOfSoup:

You both raised the question about whether immigrants sponsoring parents and grandparents was a significant issue. Your questions made me realize that raising this issue was a distraction from the main issue – that immigrants, of whatever age when they arrive, will grow older. The Robson and Mahboubi study was not based on the age composition of immigrants changing – i.e. it did not assume an increasing number of parents and grandparents being sponsored over time. I have thus edited the post to modify that section and focus only on the aging of immigrants, with a footnote indicating the modification and directing the interested reader to these comments.

On this question, a few clarifications may be useful:

i. With respect to sponsored parents and grandparents, while the sponsoring family member must commit to supporting their parents or grandparents, this does not make the parents or grandparents ineligible for Old Age Security – the only criteria is that the parents or grandparents will have to have been resident in Canada for ten years before reaching age 65.

ii. They will be eligible for coverage by the health care plan in whichever province they reside.

iii. While it is true that there currently is a cap of 10,000 per year in this program, the cap is strictly a policy decision of the government. Over time, as the number of families which wish to sponsor their parents or grandparents grows, the pressure on the government to raise that limit will become stronger. Does anyone want to bet that no government will ever bend to the political pressure to raise the cap?

I would also draw your attention to Tom Stringham’s point. Many immigrants will feel an obligation to look after their parents and grandparents whether or not they gain permanent resident status in Canada. If they remain in the home country, the children and grandchildren in Canada will be carrying an additional financial burden which will need to be, at least implicitly, taken into account in determining how much of Canada’s senior promise they can afford to fund. This is discussed in more detail here: https://financesofthenation.ca/2021/09/28/increased-immigration-alone-cannot-solve-canadas-aging-issues/

Segmentation Fault, with respect to your second point, let me draw a bit of a larger context around how I am approaching the issue.

I am not saying we should have no immigration into Canada. I think the relatively healthy levels we had during the 90s and early 00s were a net benefit to Canada. What I am raising concerns about is the much higher levels between 2016-24, and the arguments for continuing higher immigration levels going forward. Yes, there is a reduction in the OAD ratio from higher levels of immigration. But there are also costs of those higher immigration levels in terms of reduced bargaining power for workers, businesses overreliance on cheap labour as opposed to investing in innovation and increased productivity, exacerbating our housing crisis, putting pressure on our health care, education and social service programs, and putting more pressure on our transportation infrastructure. There is presumably some “optimal” level of immigration, difficult as that may be to agree on. But it can’t be the case that more is always better.

This last point segues into CupOfSoup’s second question: what is the “right” level of immigration? I will be discussing this in subsequent posts. I will make two points here:

i. Note above that I said I was comfortable with levels in the late 90s and early 00s. Had Canada’s population continued to grow at the average rate of 1995-2005, its population in 2024 would have been 39.3 million. Instead, it was 42.3 million. This has put significant pressures on the labour and housing markets, as well as on government programs. It will probably take some years of below trend growth to unwind this.

ii. Beyond this transition period, I think we should be setting our immigration targets based on the health of our labour markets (i.e. is the real average/median wage growing at a healthy rate?), and of our housing markets (i.e. how affordable is a family-friendly house for Canadians in the 20-39 age group?).

Having said all of that, CupOfSoup, I think you are probably in the right range (0.5-1%) - though I would lean the lower half of that range - after we have unwound the excesses of the last few years.

Thank you all for your comments and questions. I learn a lot from them.

Valid use of the term Ponzi scheme.