Some Facts Just Ain’t So

Some Caution on Wind and Solar Energy Please

“It ain’t what you don’t know that gets you into trouble. It’s what you know for sure that just ain’t so.”

Mark Twain

A Fable

O ran a restaurant and needed to hire a new cook. Two individuals were interviewed – B and G. They both looked good on paper. Both demonstrated their cooking skills, and seemed equally competent. When asked what wage they required, B quoted $50/hour, G quoted $25/hour. Without doing any reference checks, O offered G the job. G accepted the offer and then handed O a 23-page contract. O happily signed, without reviewing, because G’s wage would be so much lower. “I’ll have the lowest cook costs in the industry,” O said to himself, “I am going to clean up!”

The first couple of weeks went quite well. Then G submitted the first invoice. In addition to the total for wages, the invoice had a $100/night transportation charge added to it. “What’s this?” said O. “That’s the cost of my getting to the restaurant,” replied G, “I live quite far away, and I need to have that cost covered. Didn’t you read the contract? It’s spelled out quite clearly on page 9.” O wasn’t very happy with that, but he felt he didn’t have any alternative because he had signed the contract. So, every night, in addition to paying G the $150 for 6 hours of work, he had to pay an additional $100. G didn’t look like such a bargain anymore. Chock it up to experience.

Fridays were always O’s busiest day of the week. The next Friday G was nowhere to be seen when O opened up the restaurant. After an anxious wait, O called up and asked where G was. “Oh, I didn’t feel like coming into work today,” G replied. “But I have a contract with you,” replied O. “Yes, you do, and if you look on page 12, you will see that, at my sole discretion, I can decide not to work whenever I choose to, and you have no recourse against me,” G said.

In a panic, O called up B, asking if B could fill in. There was a long pause on the line, and then B said, “Yea, I can come in, but it will be $100/hour.” “But, you quoted me $50/hour before!” a somewhat angry O sputtered. “Yes I did, but that was on the presumption that I would have steady work with you. If you are only going to use me once-in-a-while, my rate is $100/hour. Do you need a cook or don’t you?” O didn’t really have much choice, and agreed to B’s terms.

When G submitted the next invoice, there was no charge for the missed Friday, but there was a charge for a Monday. O was incensed – the restaurant wasn’t open on Mondays. “Why the hell did you charge me for a last Monday?!” O demanded. “Well, that’s simple,” G responded, “I showed up on Monday and was prepared to work.” “But, the restaurant doesn’t open on Mondays!” “Doesn’t matter. Look at page 17 of the contract. It says I get paid whenever I show up for work, whether you need me or not.”

Sadly, O’s restaurant went out of business after a few months. With the extra costs associated with G’s contract, O was no longer able to cover costs. O tried raising prices, but that led to a loss of customers, and the losses grew. O’s banker foreclosed, and that was the end of the restaurant.

But That’s an Absurd Fable!

You may think so, but stay with me.

The discussions around the energy transition are constantly peppered with assertions that renewable energy (wind and solar) have become the lowest cost sources of energy. This is stated with an authority that leaves no room for doubt that a rapid energy transition, which will be dominated by renewables, is upon us. And only unreconstructed fossil-heads would think otherwise.

So that people don’t completely blow a gasket, let me stipulate upfront the following points:

· There have been significant advances in reducing the costs of wind and, especially, solar, generation of electricity over the last twenty years.

· Advances in battery technology have significantly reduced the cost of short-term energy storage.

· Wind and solar can be a useful part of the electricity generation mix.

· Electricity is significantly more efficient than fossil fuel combustion in many final use applications.

But none of that justifies the wind and solar triumphalism that is rampant in energy transition discussions. The assertion that renewable energy is the cheapest source of energy is a significant misrepresentation of the costs of an energy system based predominantly on wind and solar.

In fact, this assertion is about as valid as O’s belief that G was the cheapest cook available. At a superficial level, $25/hour is cheaper than $50/hour. But, when all of the additional costs are added in, G definitely wasn’t the cheapest cook available. Let’s examine the parallels between G and wind and solar.

It All Started with Something Called the Levelized Cost of Energy

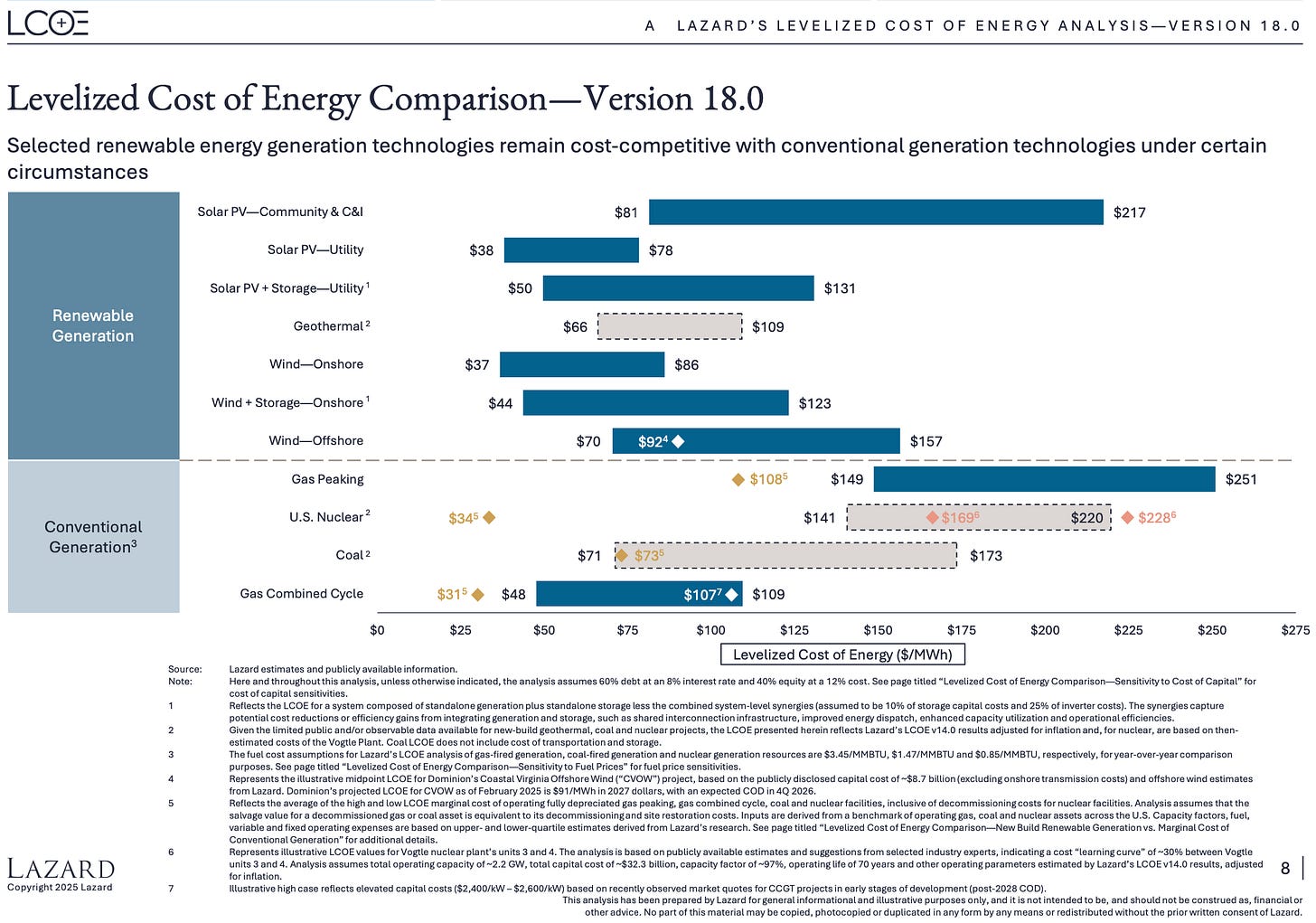

Virtually all of the claims that wind and solar are the cheapest sources of energy are based on a concept known as the levelized cost of energy (LCOE) which estimates the average costs of different ways of generating electricity.[1] The most widely cited source is an annual analysis done for the U.S. by the financial services firm Lazard.[2] Figure 1 below is Lazard’s summary of its most recent calculations.

That is a busy graph, but for now just look at the blue bars for Solar PV-Utility, Wind-Onshore, and Gas Combined Cycle. Those three bars represent the range of estimated costs for solar, wind, and natural gas generation. While there is a wide range in each estimate, it does appear that, on average, solar and wind would be cheaper than natural gas, and, indeed, cheaper than any of the other alternatives.

These Lazard calculations, and others following a similar methodology, are the basis for the repeated assertions that renewables have become the cheapest sources of energy.

But, It’s More Complicated Than That

LCOE provides the best estimates of the costs of generating electricity at a particular site, but it does not include the costs of integrating that electricity into a power system.

LCOE does not include the costs of transmitting the electricity from the generation site to the end use customer. For renewable facilities located close to existing lines with capacity for additional transmission, this additional cost need not be significant. But, as more renewable capacity is added to the system, such “sweet spots” will be already occupied, and additional renewable sites will be more broadly distributed and located farther away from high-energy use areas, leading to higher transmission costs. Studies in the U.S. have estimated that systems with very high levels of renewable energy would be impossible to implement without doubling or tripling the size and scale of that nation’s transmission system.[3]

In our fable above, G had an add-on to the hourly rate for transportation costs. A power system has to add on the transmission costs associated with wind and solar.

The major challenge of renewables, however, is that they are intermittent sources of energy – they do not generate electricity when the wind doesn’t blow, and the sun doesn’t shine. But a reliable system needs to provide electricity 24 hours a day, 365 days of the year, and in different amounts at different times of the day and at different times of the year. To provide this, the system needs a significant proportion of its capacity to be dispatchable – capable of being ramped up or down on an as-needed basis. Wind and solar are incapable of doing this.

So long as the proportion of total system capacity provided by wind and solar is relatively small, this can be accommodated with other generating sources that are dispatchable– e.g., hydro, natural gas, and coal. This becomes increasingly difficult as wind and solar provides larger proportions of total system capacity.

One solution to this is additional capacity of dispatchable power as the backup for when wind and solar are not generating sufficient power – for example, a natural gas “peaking” plant. But because the annual output of the peaking plant will only be a fraction of what it would be if it was providing baseload power, its per unit costs will be high, as its capital and maintenance costs will be spread over smaller volumes. Look back at Figure 1 and locate the blue bar for Gas Peaking, and note how much more expensive it is than the Gas Combined Cycle.

This is analogous to our fable where B charged a higher wage/hour if O was not going to provide steady employment.

Proponents of the renewable shift counter this by arguing that improvements in battery technology mean that we can dispense with backup power, and instead just build sufficient battery storage as the backup for renewable power – the standard suggestion is for four hours of backup battery storage. But a fully reliable system would require multiple days, not hours of backup, to reflect the fact that wind and solar deficiencies can occur for extended periods of time, not just a predictable few hours a day.[4] In addition to a large amount of storage, a system based predominantly on renewables would need total generation capacity that would be significantly above annual peak requirements in order to not only meet those requirements, but also to recharge the batteries after they have been used to back up a period of insufficient wind and solar output. This all will be much more expensive than a “batteries have gotten much cheaper” wave of the hand would suggest.

Just as wind and solar may not be generating power when it is needed, they may also generate power when it is not needed. Different electricity systems manage this differently. Some give preference to wind and solar, and force other sources to curtail, which will make the per unit costs of those other sources higher. Some pay the wind and solar operators to not feed their power into the grid. Some accept the power and then sell it to a neighbouring system – as does, for example, Ontario’s Independent Electricity System Operator (IESO) – quite often at a loss.

This is analogous to our fable when G showed up for work even though the restaurant wasn’t open. There will be costs to the system associated with it.

These Costs Add Up

How much does all of this change the relative costs of wind and solar? The answer to that is “it’s complicated” – it will vary from system to system, depending on each system’s mix of electricity sources and other factors. This is already a long post, so I will restrict the discussion to two estimates.

The first estimate is from Lazard. In its most recent analysis, Lazard estimated the “firming costs” for wind and solar in the different regional grids in the U.S. The firming cost is the cost of having backup power available for times when wind and solar are not generating electricity. Lazard’s estimate of these firming costs range between $14-73/MWh for wind and $42-86/MWh for solar. Look back at Figure 1 and add these to the blue bars for wind and solar. Adding in these firming costs, it is not at all clear that the claim that solar and wind are the cheapest sources of energy remains valid. It is curious that Lazard’s analysis of firming costs doesn’t receive as much attention as its analysis of LCOE.

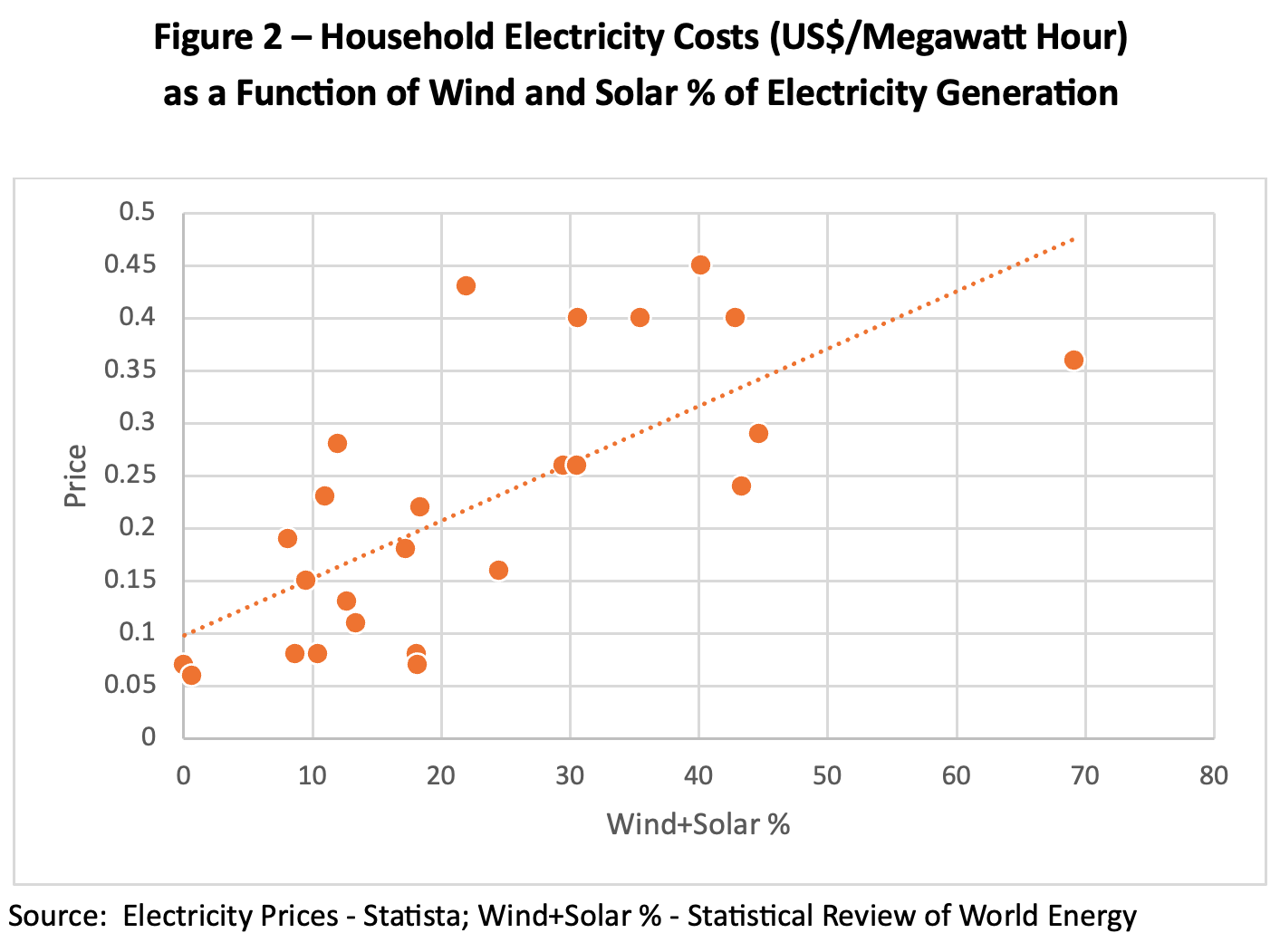

The second estimate is a quick and dirty comparison of household electricity prices with the percentage of electricity generated by wind and solar for 25 countries. The comparison is shown in Figure 2 below.

If wind and solar were truly the cheapest source of energy, we would expect the relationship between price and the renewable percentage to be downward sloping – as the wind and solar percentage rises, the price of electricity should fall. In fact, the fitted dotted line shows the exact opposite.[6]

The countries with less than twenty percent wind and solar generation had an average price of US$0.138 per kilowatt hour; the countries with more than twenty percent wind and solar generation had an average price of US$0.329 per kilowatt hour.

This was not an exercise in cherry-picking. It was based on the 25 countries that Statista had on its publicly available website.[7]

The widely asserted claim that electricity systems based predominantly on wind and solar will be low cost is not borne out by empirical evidence.

Some facts just ain’t so.

Discussion

Notwithstanding my stipulations above, I fear some gaskets may have been blown. So, let’s be clear about what I am saying and what I am not saying.

I am not saying that wind a solar cannot be a useful part of the electricity mix. For certain uses, and in certain locations one or the other may be the best choice to generate electricity. And, up to a certain percentage, the intermittency of wind and solar can probably be managed within an electricity system without significant additional costs, and may, indeed, be relatively low-cost additions to the system.

What I am saying is that, with today’s technologies, transitioning to an electricity system that is powered predominantly by wind and solar would be foolish. The amount of wind and solar power that can be economically integrated will vary from system to system, but it would appear that costs start rising after the wind and solar percentage is higher than no more than 25 percent. European countries that have blown by this guardrail can be considered the canaries in the coal mine solar farm, with the deindustrialization[7] and energy poverty[8] problems that have arisen from high energy costs.

I am not saying that electrification of many activities will not be an important part of the decarbonization path. Electricity is significantly more efficient than fossil fuels in many - though not all – end use applications. The challenge will be building out an electricity system that is reliable, inexpensive and less carbon intense. We will look at what that might look like in a future post.

In the meantime, let’s remind ourselves of Mark Twain’s wisdom.

[1] Some sources refer to this as the levelized cost of electricity, which is actually a more accurate description. Lazard, however, uses energy as its e-word, and that has become the more common usage.

[2] https://www.lazard.com/research-insights/levelized-cost-of-energyplus-lcoeplus/

[3] https://www.esig.energy/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Transmission-Planning-White-Paper.pdf

[4] The Germans even have a term for this – “dunkelflaute” – a period of low or no wind and sunshine. These periods generally happen between October and February. They can last from several hours to several days. In November 2024 one lasted for 12 consecutive days.

[5] https://www.statista.com/statistics/263492/electricity-prices-in-selected-countries/?srsltid=AfmBOoo6w7r-jE0-Nay482h_W7tA5aZ8p9xZ-iBUoPzOUEmcQrcMuTHe

[6] For the statistical nerds, the positive relationship between price and the solar+wind percentage is significant at the 99.9 percent level.

[7] https://www.forbes.com/sites/jimvinoski/2024/02/29/german-deindustrialization-is-a-wake-up-call-for-us-manufacturers/

[8] https://www.endfuelpoverty.org.uk/fuel-poverty-statistics-show-12-million-households-struggling/

Don, I like how you deployed a fable to dispel a myth! (Sam Clemens/Mark Twain would surely have enjoyed it too.) Your analogy works really well to illustrate and clarify the technicalities that people seldom hear about or consider.

Another downside to over-reliance on renewables for grid-scale power generation is that they don’t provide grid (or system) “inertia,” which can be thought of as a grid’s shock-absorber and comes built-in with the large rotating turbines of conventional generating systems (e.g., gas, hydro, and nuclear). While synthetic forms of inertia are being developed as add-ons for wind/solar/battery systems, they add substantially to the cost of renewables.

Last but not least: consider the ‘cost’ (in financial AND human terms) of more frequent or widespread “blackouts.” I did a quick AI query about the major one in Europe earlier this year (though I already knew the answer). Here’s what “Gemini” had to say: “a consensus is emerging among grid experts and in preliminary reports that a lack of system inertia was a critical contributing factor to the severity and rapid collapse of the Spanish and Portuguese power grid during the major failure of April 28, 2025.”

I am really looking forward to your next article on possible solutions! I really like how you have demonstrated in your earlier articles about how low energy costs are one of the most important things that have contributed to rising living standards and why high energy costs can also have the effect of lower living standards. I actually didn’t know that the former was true. It’s something i never spent any time thinking about it.