Four Blindingly Obvious Factors to Pay Attention to in the Energy Transition

Have you ever witnessed the anger of the good shopkeeper, James Goodfellow, when his careless son has happened to break a pane of glass? If you have been present at such a scene, you will most assuredly bear witness to the fact that every one of the spectators, were there even thirty of them, by common consent apparently, offered the unfortunate owner this invariable consolation – "It is an ill wind that blows nobody good. Everybody must live, and what would become of the glaziers if panes of glass were never broken?"

Frederic Bastiat

In the previous post[1] we showed how the incredible increase in global living standards over the past 200 years could not have happened without the use of ever more inanimate energy, ever more efficiently. Stated baldly: there are no high-income-low-energy countries.

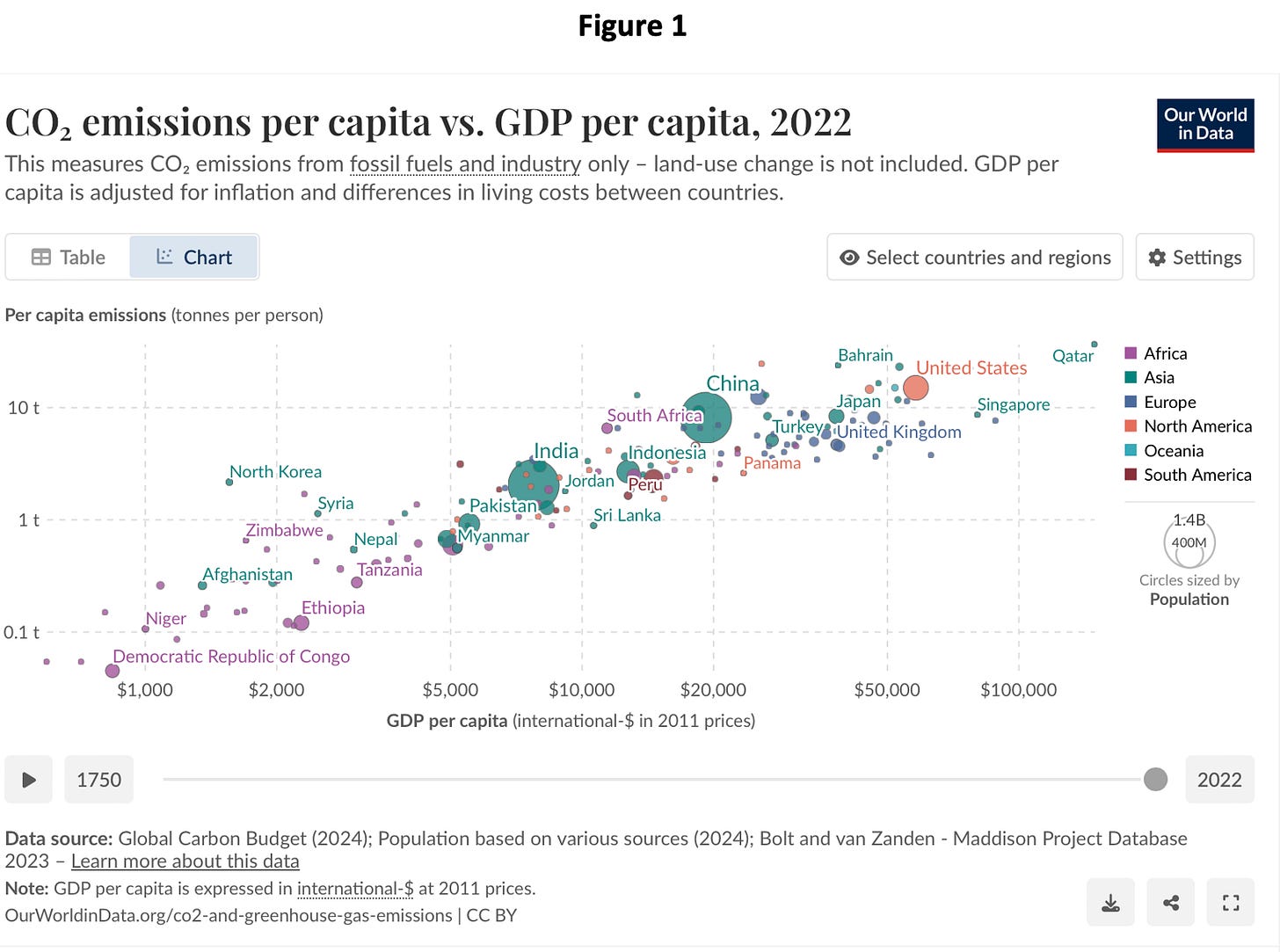

The dilemma facing the world is that, because the world’s energy system is still primarily based on carbon fuels, higher standards of living have been accompanied by higher greenhouse gas emissions, as demonstrated by Figure 1 below, which shows the relationship between GDP per capita and CO2 emissions per capita.

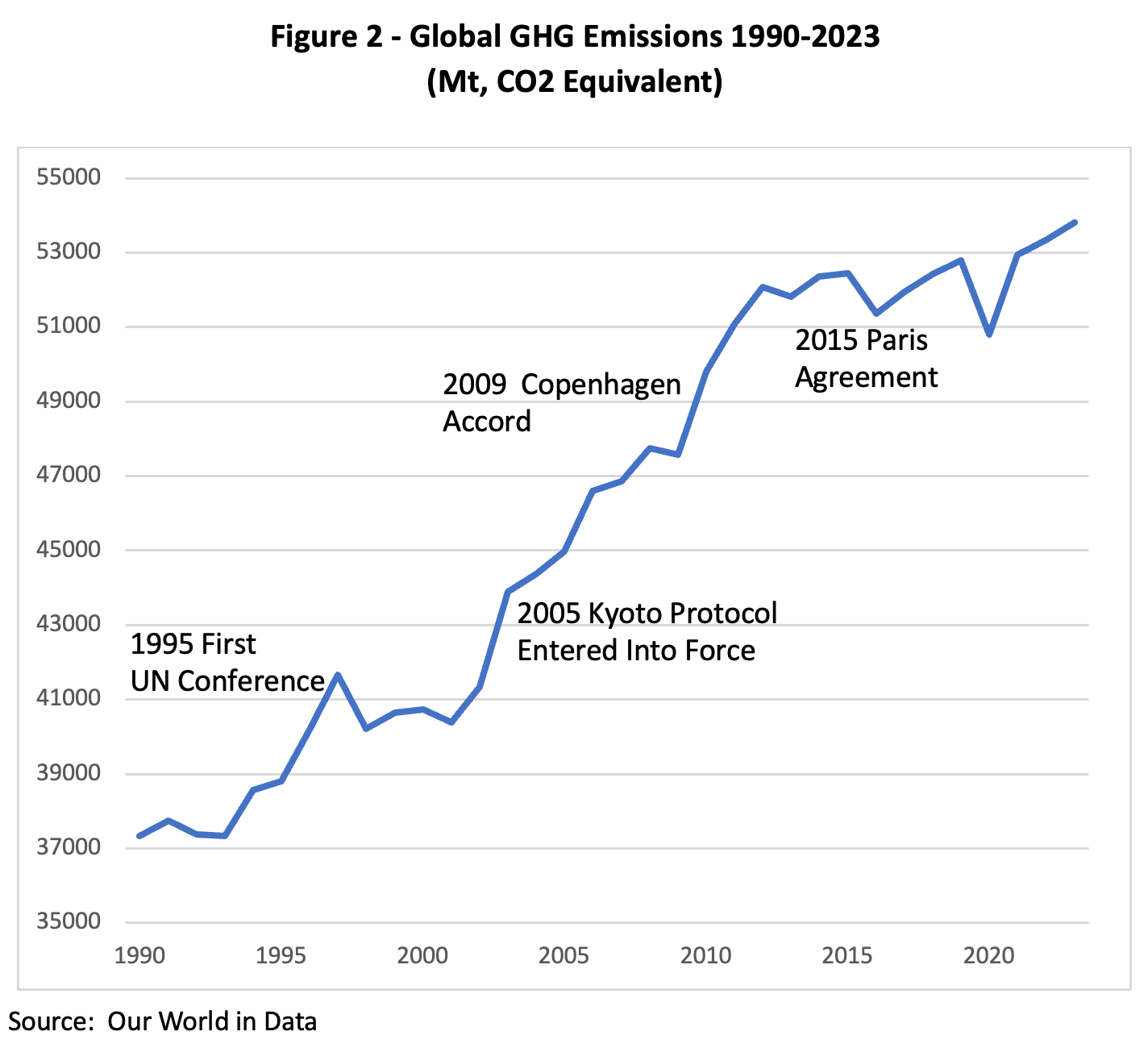

For the more than 30 years countries have been working through the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. At successive Conferences of the Parties to the UNFCCC, ever-bolder commitments to reduce emissions have been made, but there seems to be relatively little to show for it, as demonstrated by Figure 2 below, reproduced from the previous post.

We suggested that an important reason for this failure to deliver is that the commitments have not been informed by an adequate level of energy literacy.

In today’s post we will look at four core components of energy literacy. For fun, we call them blindingly obvious factors.

1. The Effective Cost of Energy Is as Important as the Amount of Energy Consumed.

In the previous post we saw how the incredible improvement in global standards of living was intimately connected to the significant increase in inanimate energy humans have utilized. It is important to understand that this was not just a function of a steady increase in the amount of energy utilized, but also a function of a steady reduction in the effective cost that energy.

The effective cost of energy entails the costs of extracting or generating primary energy, as well as the efficiency with which the primary energy is converted to the provision of useful services – e.g., substituting for human and animal muscle power in agriculture and industry, or providing higher quality light than could be provided with candles and torches.

Since the 1700s there has been a steady reduction in the effective cost of energy services, through ongoing innovation all along the energy supply chain - the development of additional forms of energy; more efficient methods of extracting or generating energy; and more efficient utilization of energy. Without this ongoing innovation, the improvement in living standards would have stalled out after the early stages of the industrial revolution, which was essentially an exercise in the relatively inefficient utilization of coal.

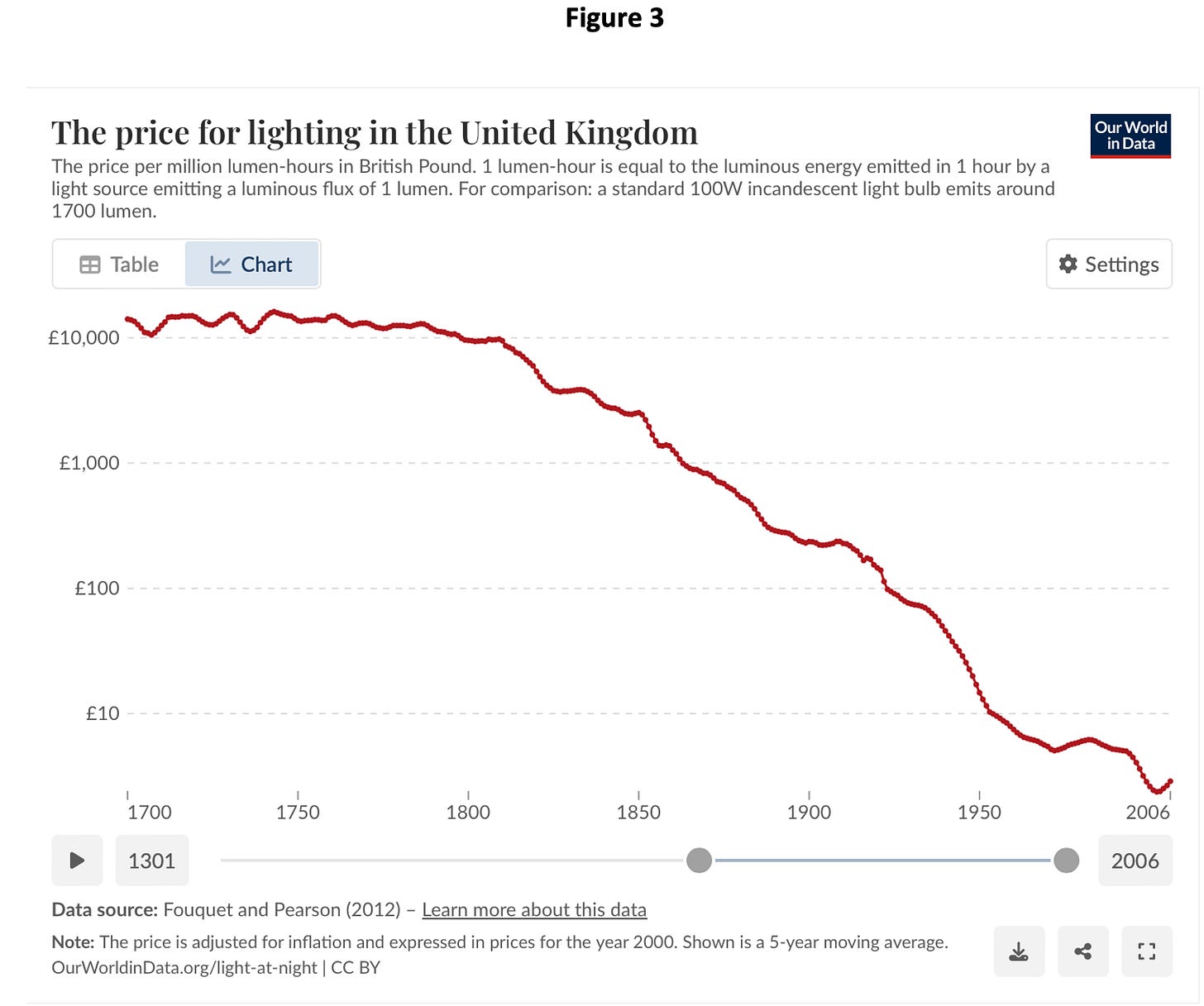

A classic example of this continuing innovation is provided by the evolution of lighting. Before the industrial revolution, light was provided predominantly by candles made from animal fat. The production of candles was labour-intensive, the quality of light provided was not great, and the air quality kind of stunk. At the start of the nineteenth century, gas lamps began to be utilized. Then came electricity, then Edison’s light bulb, then fluorescent light, then halogen light and then LED light, all accompanied by continuing reductions in the cost of electricity. Figure 3 below shows the net result of all of this in terms of the real cost per lumen-hour in the United Kingdom. The price of light in 1700 was almost 5000 times more expensive than it was in 2006!

Why is it important to understand the significance of the effective cost of energy? For two key reasons.

First of all, because the substitution of energy for human muscle and brain power is the key to the whole story of progress over the past 200 years. The lower the effective cost of energy, the greater can be the degree of substitution of energy for human muscle and brain power. If, on the other hand, the effective cost of energy were to start rising, the progress machine would slow down, and could even go into reverse.

Blindingly obvious? Perhaps, but it doesn’t always seem to be at the centre of discussions about the energy transition.

And the second reason? That’s next.

2. Total Expenditures on Energy Are Not Insignificant

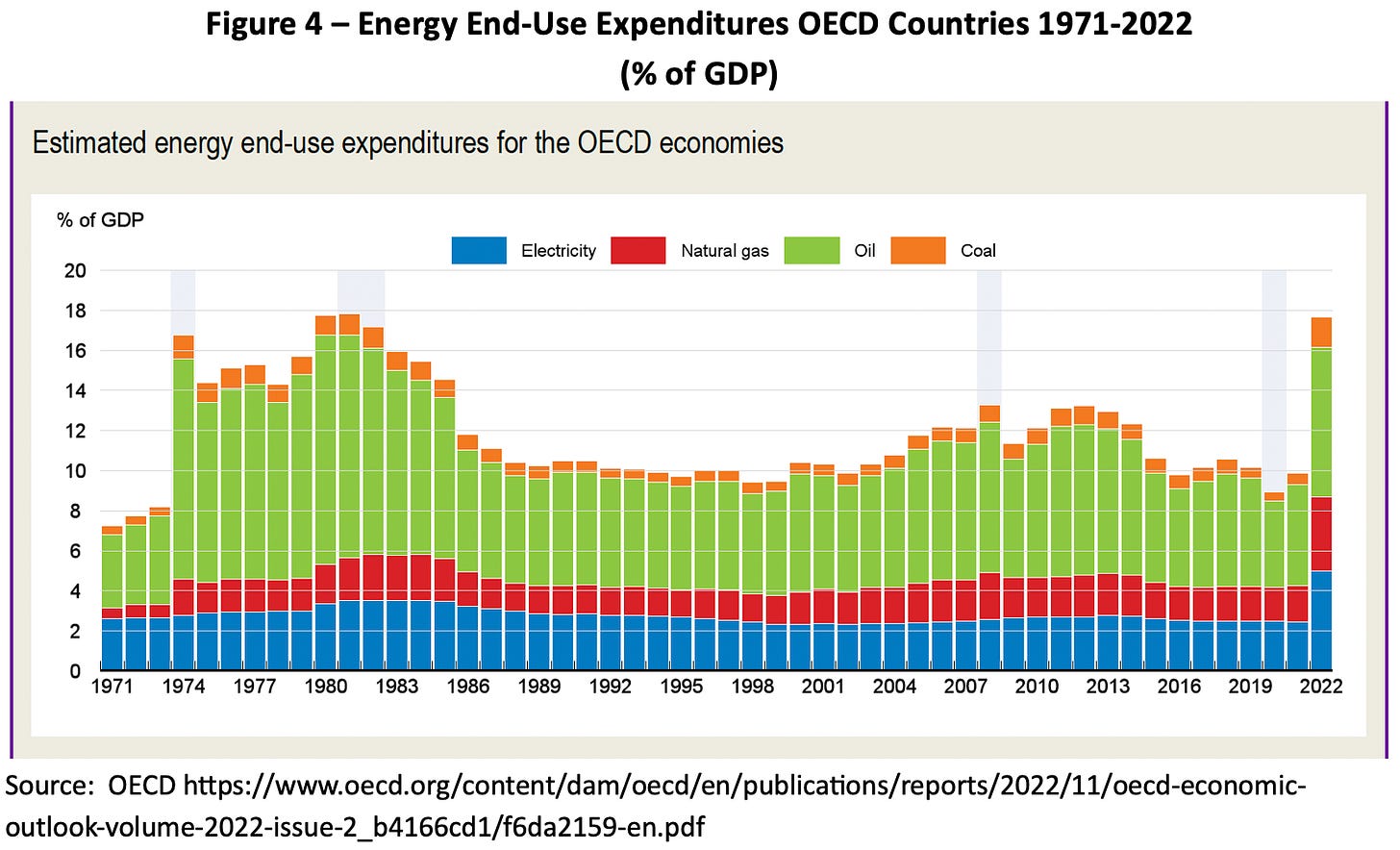

Figure 4 below shows the OECD’s estimate of total end-use expenditures for energy as a percentage of GDP in the OECD countries. For any individual country, end-use expenditures exclude energy exports. In essence, this measure shows how much our use of energy costs us, in terms of the percentage of our income.

Over the period 1971-2022 expenditures averaged 11.9% of GDP, with a low of 7.2% in 1971 and highs of 17.8% in 1981 and 17.7% in 2022. The peaks are clearly related to geopolitical disruptions – in the Middle East in 1973 and 1979 and the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022 – but other than that there is no apparent trend.

The equivalent figure for the U.S. over the 1970-2023 period averaged 8.1%, with a low of 4.7% in 2020 (reflecting the Covid recession) and a high of 13.3% in 1981.[2]

Statistics Canada does not seem to calculate an equivalent figure for Canada, so we are forced to make some order-of-magnitude conjectures. If the equivalent number for Canada was in the neighbourhood of 8% (i.e., that of the U.S.), in 2024 end-use expenditures would be in the neighbourhood the $5900 for every Canadian.

Why is it important to understand that total expenditures on end-use energy are not insignificant? Because major changes in energy prices will have significant impacts on the standard of living of Canadians. If energy prices rise because of external factors – e.g., changes in world oil prices – that is beyond the control of Canada. But if changes are the result of Canadian policy changes – e.g., measures to reduce greenhouse gas emissions – then we should pay attention to it.

Blindingly obvious? Perhaps, but the evidence that it figures prominently in policy makers’ considerations is spotty.[3]

3. Putting Extraordinary Restrictions on the Oil and Gas Sector Will Make Canadians Poorer

Canada’s oil and gas sector account for a disproportionate share of GHG emissions. In 2023, upstream oil and gas accounted for 25% of Canada’s emissions. From one perspective, it is perhaps understandable why this sector would be singled out for extraordinary restrictions. The extraordinary measures, either in place or proposed, include the oil tanker ban on British Columbia’s north coast, changes in the environmental assessment process that are particularly onerous on long linear projects such as pipelines, and the cap on oil and gas emissions in addition to the industrial carbon tax that all heavy industry is subject to.

A different perspective, however, would note that the oil and gas sector contributes disproportionately to Canada’s national income. It pays significantly higher than average wages, and contributes disproportionately to government revenues. Elsewhere, I have estimated the “counterfactual’ of Canada having no oil and gas sector.[4] I conservatively estimated that in 2019 Canada’s income would have been 6 percent lower – which would be felt primarily in lower average wages across Canada. The federal government’s deficit in 2019 would have been $42 billion higher - more than doubling that year’s pre-Covid deficit.

One may want to argue that putting extraordinary restrictions on the oil and gas sector is the right thing to do. But trying to pretend this won’t have a negative impact on Canadians’ incomes is being more than a little economical with the truth.

Blindingly obvious? Perhaps, but many advocates try to wave it away with bromides about “just transition” and “green jobs.”

4. Rebranding Costs as “Opportunities” Does Not Make the Costs Go Away

Before the change of regime, the federal government estimated that Canada would have to spend $125-140 billion a year - $3.3-3.6 trillion between now and 2050 - in order to meet its net zero target. That annual spend would be 4.1-4.6% of GDP. To put that in perspective, in 2024 Canada total spend on energy infrastructure was $37 billion – 1.2% of GDP.[5]

Of course, the official label isn’t “spend,” but rather “invest.” And we should all know that this presents an incredible “opportunity.” The former Minister of the Environment told us so:

“Building a cleaner economy is not only an environmental imperative, it is a major economic opportunity.”

This thinking reflects Bastiat’s broken window fallacy.[6] Anything that imposes extra costs on society seems to stimulate economic activity, and thus may be portrayed as an opportunity. But we must ask where the funds for the $125-140 billion per year will come from. From additional taxes? From reduced government spending on other programs? From increased levels of government borrowings? From private investors who will expect to receive a return on that investment, presumably from the ratepayers using the energy?

One may call the additional spending required an investment, or even an opportunity if one wants. That does not mean that it isn’t a cost. One may argue that it is a necessary cost. But it still must be paid by Canadians.

Blindingly obvious? Perhaps, yet the desire to rebrand costs as opportunities continues.

Concluding Comments

Climate change is a serious issue, and it is important that the global community, collectively, figures out how to reduce emissions to the greatest practical extent. And Canada must shoulder its fair share of that effort.

But, if we are going to develop a decarbonization pathway that is sustainable, that pathway needs to be energy literate. This is necessary to ensure that we pursue the most cost-effective pathway to decarbonization. But even more important, in my opinion, is that this will be necessary to maintain public support for that pathway.

In the 2022 piece that I mentioned above I wrote:

“If public support for decarbonization is to be maintained over the multiple decades during which a grand decarbonization project will unfold, it is essential governments are as candid as possible about the impacts this will entail.”

Public concern about climate change declined last year.[7] It is also well down the list of issues that Canadians identify as the most important – only 16 percent of voters rate climate change and the environment as one of the three most important issues facing Canada.[8] There are multiple reasons for that, but the growing realization that decarbonization is less an opportunity than an obligation is amongst those reasons.

The next few posts will explore how greater energy literacy could suggest a better decarbonization path.

[1] https://donwright.substack.com/p/energy-illiteracy-could-kill-us?r=78jix

[2] https://www.eia.gov/totalenergy/data/browser/index.php?tbl=T01.07#/?f=M&start=200001

[3] Here’s an example to the contrary. A colleague was talking to a federal official involved in developing the Clean Electricity Regulations. The proposed regulations require all electrical utilities to stop using unabated fossil fuel generation by 2035. The colleague asked why the feds didn’t just use the carbon tax to achieve their objective. The answer was that they had considered that, but when they modeled it out, a carbon tax as high as $400/tonne was not sufficient to incent the shutdown of the unabated coal or gas plants – a tacit admission that the alternative to unabated fossil fuel generation would be more expensive than the costs of unablated fossil fuel generation with a $400/tonne carbon tax added on top. That provinces not blessed with ample hydroelectric potential would have to accept significant increases in electricity prices was apparently not a concern to the federal government intending to implement these Regulations.

[4] https://ppforum.ca/publications/do-we-really-want-to-make-canadians-poorer/ The reader may also want to review a previous post: https://donwright.substack.com/p/the-basic-arithmetic-of-canadas-standard?r=78jix

[5] https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=3610060801&pickMembers%5B0%5D=1.1&pickMembers%5B1%5D=2.1&pickMembers%5B2%5D=3.1&pickMembers%5B3%5D=4.1&pickMembers%5B4%5D=6.1&cubeTimeFrame.startYear=2020&cubeTimeFrame.endYear=2024&referencePeriods=20200101%2C20240101

[6] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Parable_of_the_broken_window

[7] https://abacusdata.ca/from-climate-action-to-immediate-relief/

[8] https://abacusdata.ca/abacus-data-poll-carneys-liberals-regain-lead-as-economy-woes-grow/

An excellent article Don. Today every government expenditure with borrowed money is called an investment (as with the Stellantis battery factory) and there are no more unaffordable costs, only exciting opportunities to create climate justice.

But we must ask where the funds for the $125-140 million per year will come from.

I think you meant to write billion here 😅