Class Matters

We have seen how Canada’s performance in increasing real wages has been dismal since the late 1970s.[1] We also noted in that post that the relatively small increases in real wages have not been shared evenly – in particular, that the percentage increase in median employment income lagged that in average employment income. In this post we will take a more granular look at how real wage increases vary.

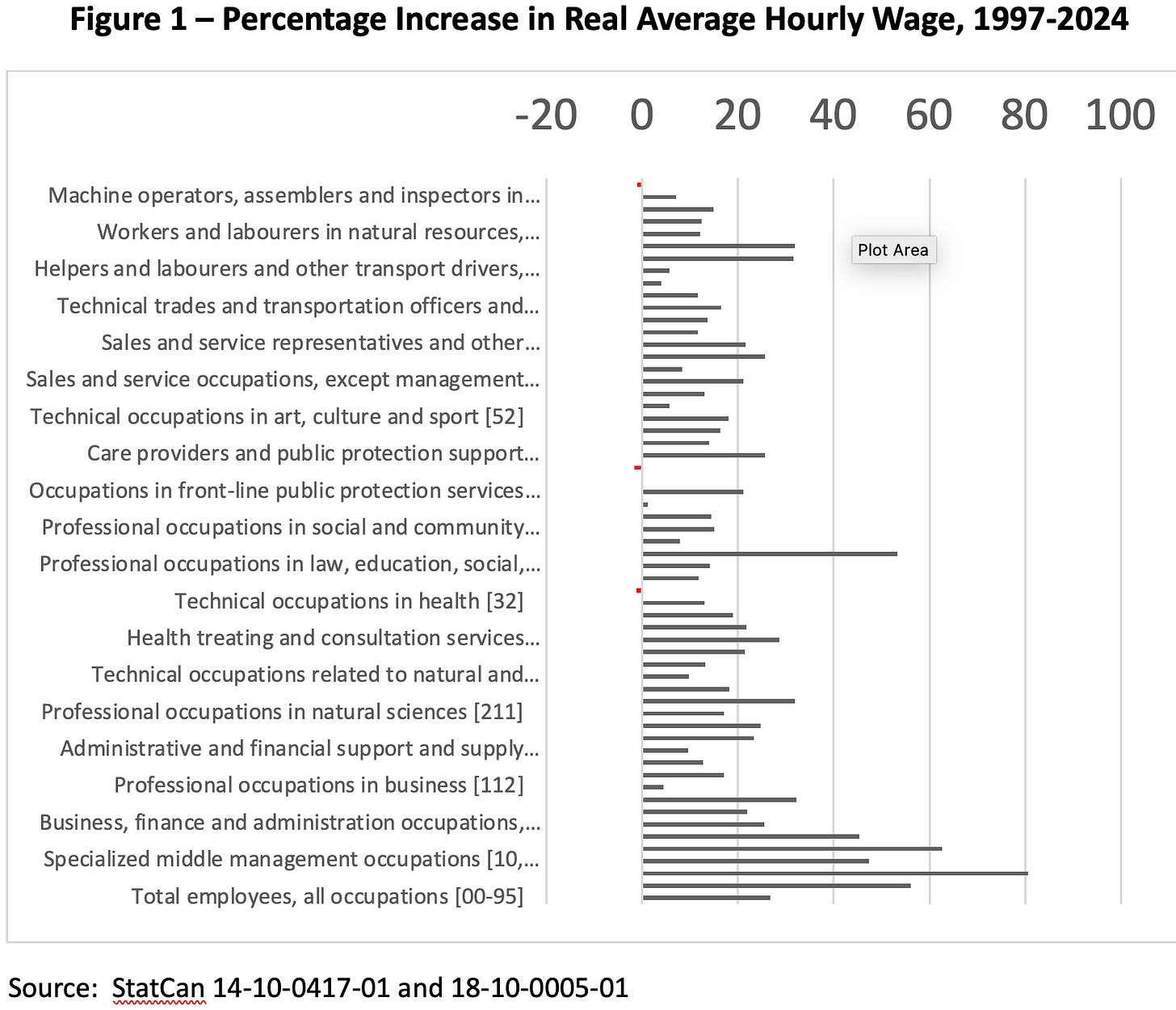

Figure 1 below shows the percentage increase in the real average hourly wage, broken down by occupations, over the period 1997-2024, which is the full range available in the Statistics Canada data series. It is a “noisy,” cluttered figure, and it is not recommended that you squint at it for very long. The point here is mostly an impressionistic one – that there is a broad range in how well different occupations have fared over this twenty-seven-year period.

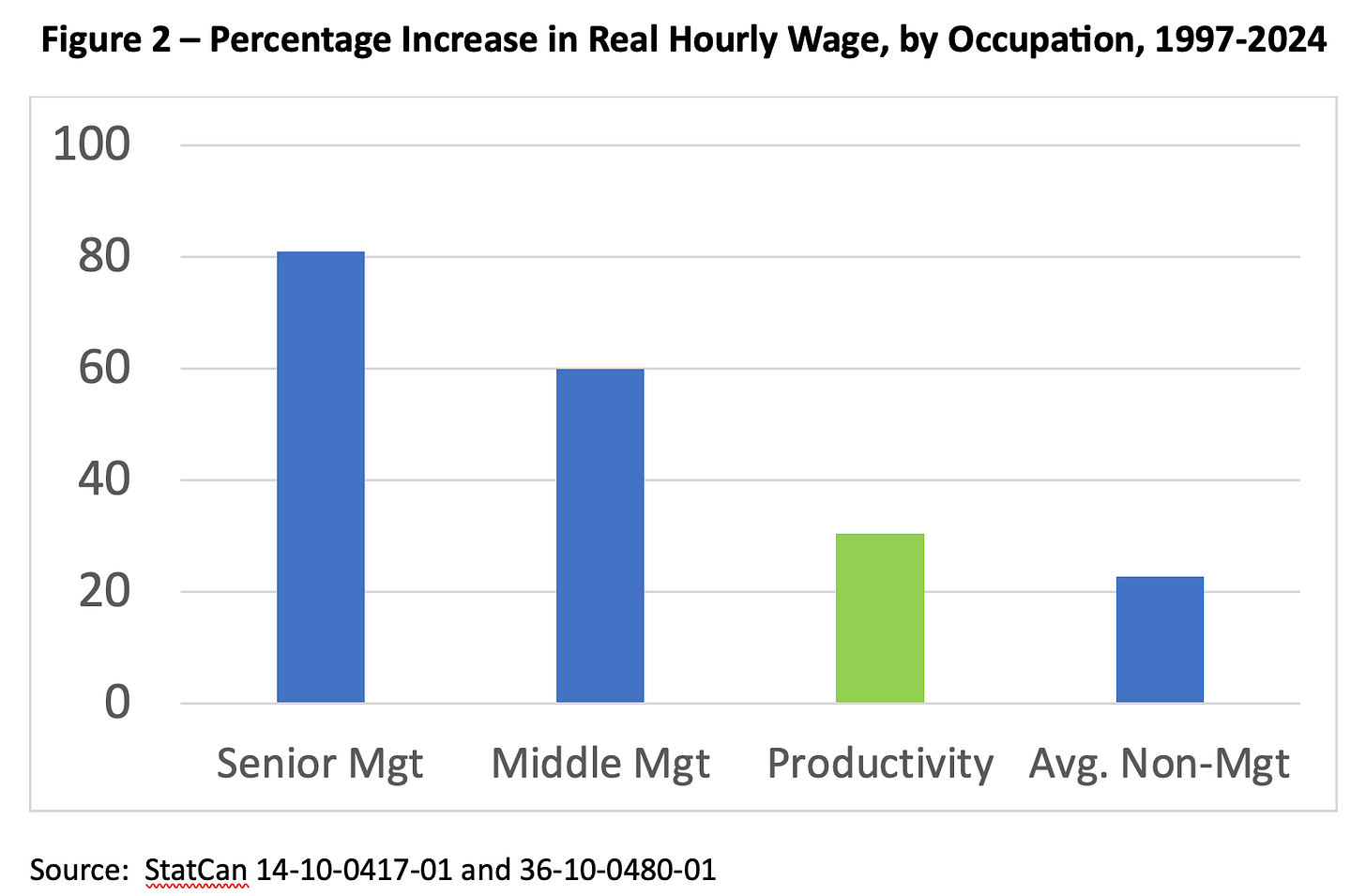

Now, let’s focus on a subset of the occupations and see what kind of story emerges. Figure 2 below shows the percentage increase in real wages for senior management, middle management and non-management employees. For comparison purposes the percentage increase in economy-wide productivity, as measured by output per hour, is included.

While the percentage increases may seem substantial, it is important to recognize that this happened over twenty-seven years. We discussed in the previous post how many years it would take to double real wages. Between 1946-76 real wages doubled every 27-28 years. At the rate of growth between 1976-2019 it would take more than 400 hundred years for real wages to double. With the series in this post, the doubling time would be 32 years for senior managers, 40 years for middle managers and 71 years on average for all non-management employees. So, better than the 1976-2019 average, but, particularly for non-management employees, a far cry from the glorious 30 years after World War II.

What to make of this? I confess that I expected to find some uneven distribution of real wage gains from this data series. But frankly, I was shocked at how stark the results were. Senior management did far better than every other occupation group. Middle management also did reasonably well. Not one other occupation group did better than these two groups. The closest other group was “professional occupations in law,” which had an increase in real wages of 53.3%. Beyond lawyers, no other occupation group saw even half the growth in real wages as did senior managers.

The full Statistics Canada definition of the group labelled senior managers is as follows:

“This group comprises senior management occupations, including legislators and senior managers in the public and private sectors.”[2]

One might say that, collectively, this group is responsible for the economic performance of the country - let’s call them the “governing class.”

How did that governing class perform? As measured by the economy’s productivity growth, not great. Between 1950-76 the average annual productivity growth was 3.6%. Between 1976-97 it was 1.4%. Between 1997-2024 it fell even further to 1%. So, the governing class presided over a continuing deterioration in Canada’s capacity to improve living standards.

Perhaps there were external factors over which the governing class had no control? Fair question. Still, it is the one group that didn’t fare that badly in terms of its increase in real incomes. Senior managers rewarded themselves with real wage growth significantly higher than the growth in productivity, while the average real wage growth of non-managerial employees was significantly lower than the growth in productivity.

One needn’t go full Karl Marx to think there is something wrong with this pattern.

Two questions to consider in this regard:

1. Is it possible that the reason why the governing class has not taken the declining rate of increase in the Canadian standard of living more seriously is that it has been largely insulated from it?[3]

2. Is it possible that Canada’s disappointing performances in increasing productivity and real wages of non-managerial employees are a function of a business model implicitly shared amongst the governing class?

The first question is left for the reader to ponder. The second question will be explored in next week’s post. For now, can we agree that we should have been paying more attention to how different occupations have fared over time – that class matters?

[1] https://donwright.substack.com/p/the-canadian-promise-is-broken?r=78jix

[2] https://www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb/p3VD.pl?Function=getVD&TVD=1322554

[3] I should acknowledge that, for most of the period 1997-2024, I would have been categorized as a member of that governing class. Mea culpa.

In the public sector, I believe management has been typically getting increases at a similar percent (or more) than the workers have negotiated. But 3% of 50K is a lot less than 3% of 125K, or 200K. So the gulf widens.

Maybe it’s time for management increases to be more structured - a certain percent up to median (?) organizational salary and then a lower percent increase on salary above that point.

I would say a clear yes to 1 and 2. It will be interesting to see how the rapid growth of AI impacts the wage stagnation/growth and whether just a subset of the governing class comes out ahead, or all of it, or if a good portion gets wiped out and maybe some of the non-white collar jobs that can't be so easily automated finally see disproportionate income gains. Will unproductive parts of the governing class find ways to escape the productivity reckoning? Everyone can't be a 10x person...